僅僅在今年5月,,《華爾街日報》(The Wall Street Journal)和《紐約時報》(New York Times)就分別發(fā)表了200多篇令人窒息的文章,要么宣布人類將面臨悲慘的災(zāi)難性結(jié)局,,要么宣布人類將獲得救贖,,這取決于所引用的專家的偏見和經(jīng)驗。

我們親身體會到圍繞人工智能的公共話語是多么聳人聽聞,。今年6月下旬舉行的第134屆首席執(zhí)行官峰會聚集了200多位來自大型公司的首席執(zhí)行官,,圍繞峰會的大量媒體報道捕捉到這些危言聳聽,,其中,42%的首席執(zhí)行官表示人工智能有可能在十年內(nèi)摧毀人類(這些首席執(zhí)行官們表達了很多有細微差別的觀點,,正如我們之前所捕捉到的那樣),。

今年夏天,在商業(yè),、政府,、學(xué)術(shù)界、媒體,、技術(shù)和公民社會對人工智能的不同看法中,,這些專家經(jīng)常各執(zhí)一詞。

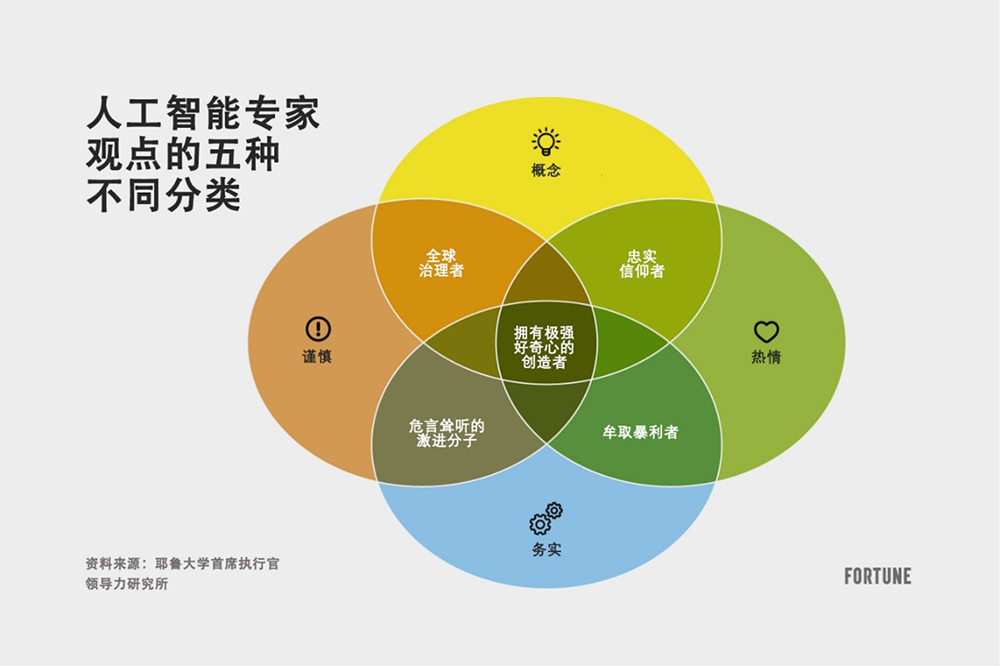

大多數(shù)人工智能專家的觀點往往分為五大不同的類別:欣喜若狂的忠實信徒,、牟取暴利者,、擁有極強好奇心的創(chuàng)造者、危言聳聽的激進分子,,以及全球治理者,。

欣喜若狂的忠實信徒:通過人工智能系統(tǒng)獲得救贖

人們長期預(yù)測的機器自學(xué)時刻,與人工智能70年來漸進式發(fā)展的現(xiàn)實截然不同,。在這樣的炒作中,,很難知道如今到底有多大的機會,以及哪些過于樂觀的預(yù)測會演變成幻想,。

通常,,那些在人工智能前沿領(lǐng)域工作時間最長的人持有更樂觀的看法,他們一生都致力于人類知識前沿領(lǐng)域的最新研究,。這些人工智能先驅(qū)是“忠實信徒”,,他們相信自己的技術(shù)具有顛覆性潛力,而且在很少有人接受一項新興技術(shù)的潛力和前景時,,他們就接受了這一點——并且遠遠早于這項技術(shù)進入主流,,因此,很難指責(zé)這些“忠實信徒”,。

對其中的一些人來說,,例如“人工智能教父”和Meta公司的首席人工智能科學(xué)家楊立昆(Yann LeCun),“毫無疑問,,機器最終會超越人類,。”與此同時,,楊立昆等人認為人工智能可能對人類構(gòu)成嚴重威脅的想法“荒謬至極”,。同樣,風(fēng)險投資家馬克·安德森對此不以為然,輕易推倒了有關(guān)人工智能的“散布恐懼和末日論的高墻”,,認為人們應(yīng)該停止擔(dān)憂,,“研發(fā)、研發(fā),、再研發(fā)”,。

但是,一意孤行,、過于樂觀可能會導(dǎo)致這些專家高估他們的技術(shù)能夠帶來的影響(也許是有意為之,,但稍后會詳細說明),并忽視其潛在的弊端和運營挑戰(zhàn),。

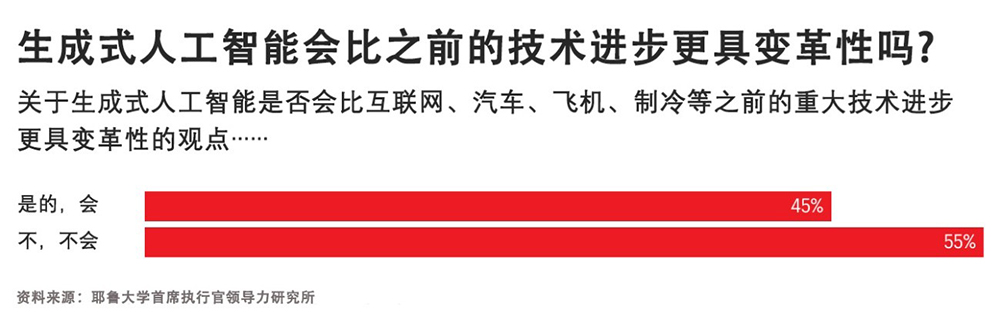

事實上,,當(dāng)我們就生成式人工智能“是否會比之前的重大技術(shù)進步,比如互聯(lián)網(wǎng),、汽車,、飛機,、制冷等的發(fā)明更具變革性”對首席執(zhí)行官們進行調(diào)查時,,大多數(shù)人回答“不會”,這表明人工智能是否會像一些永恒的樂觀主義者希望我們相信的那樣,,真正顛覆社會,,仍然存在不確定性(在很大范圍內(nèi))。

畢竟,,存在真正改變社會的技術(shù)進步,,但大多數(shù)在最初的炒作之后以失敗告終。僅僅18個月前,,許多狂熱者確信加密貨幣將改變我們的日常生活——在FTX破產(chǎn),、加密貨幣大亨薩姆·班克曼-弗里德被捕(從而名譽掃地),以及“加密貨幣的冬天”來臨之前,。

牟取暴利者:進行無厘頭炒作

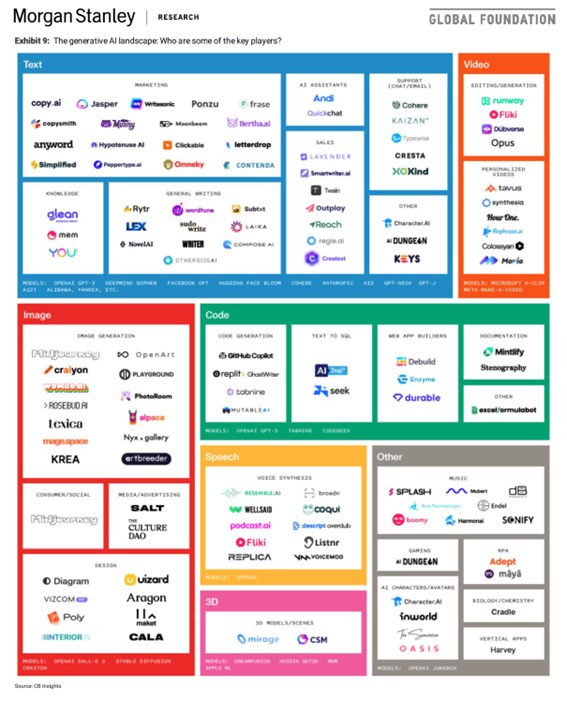

在過去的六個月里,,在參加貿(mào)易展、加入專業(yè)協(xié)會或接受新產(chǎn)品推介時,,毫無疑問會被聊天機器人的推銷所轟炸,。在ChatGPT推出的刺激下,圍繞人工智能的熱潮逐漸升溫,,渴望賺錢的企業(yè)家(是機會主義者,,但也很務(wù)實)紛紛涌入這一領(lǐng)域。

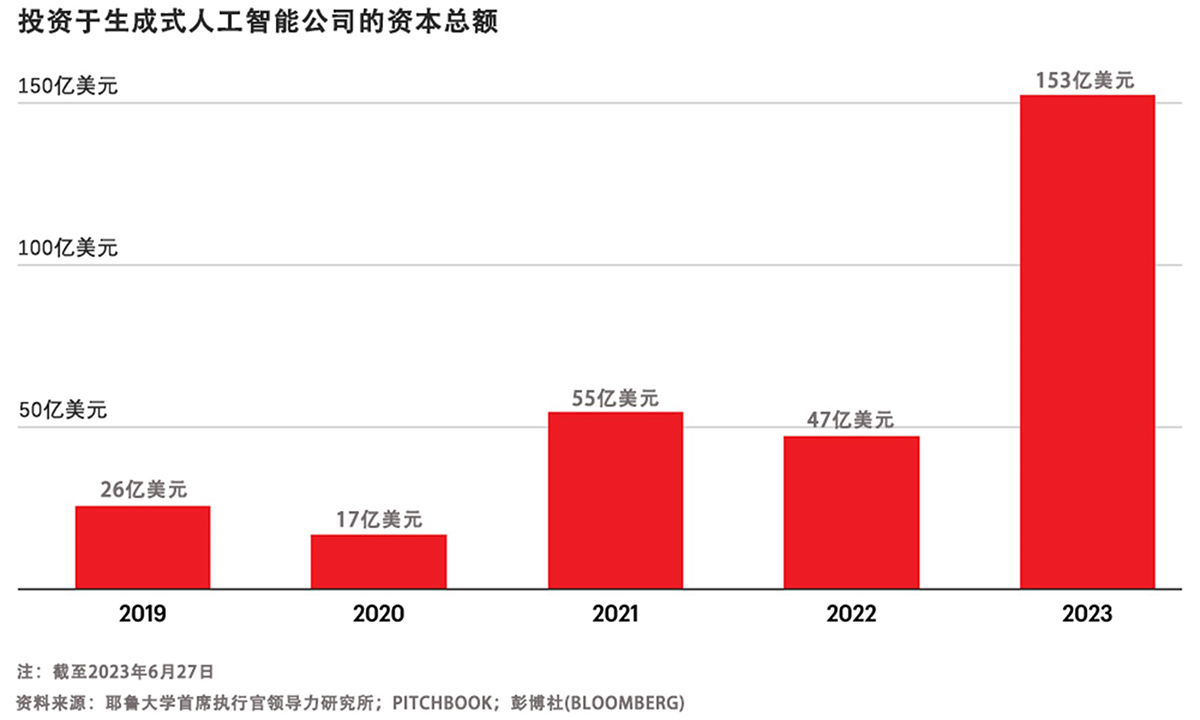

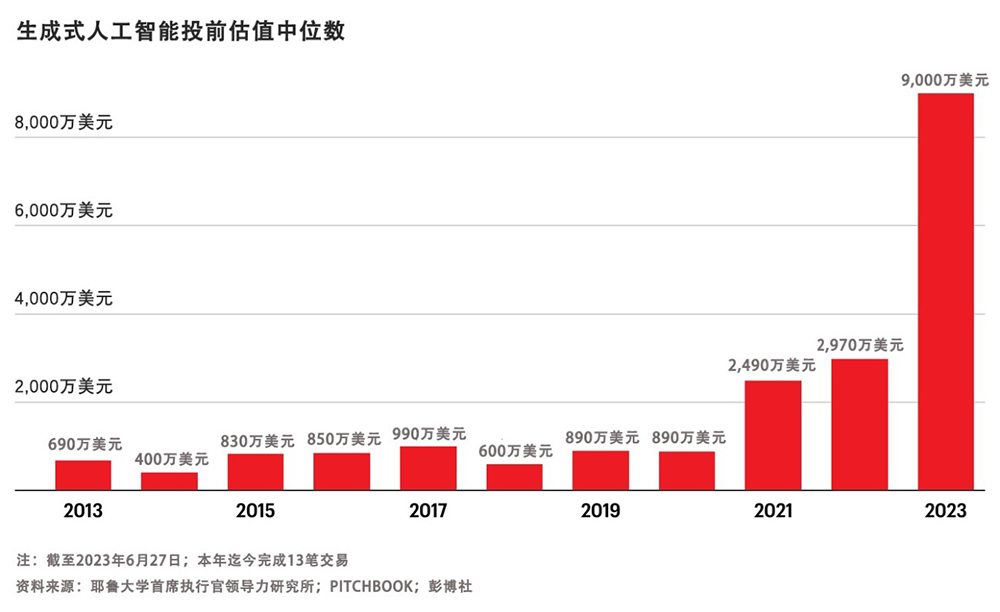

令人驚訝的是,,今年前五個月投入到生成式人工智能初創(chuàng)公司的資金比以往任何一年加起來都多,,僅在過去五個月中就有超過一半的生成式人工智能初創(chuàng)公司成立,而今年生成式人工智能的估值中位數(shù)比去年翻了一番。

也許讓人想起在互聯(lián)網(wǎng)泡沫時期,,那些希望立即提升股價的公司在其名稱中添加“.com”的日子,,如今,一夜之間,,大學(xué)生創(chuàng)辦的以人工智能為重點的初創(chuàng)公司如雨后春筍般涌現(xiàn),,這些初創(chuàng)公司的產(chǎn)品大都雷同,一些創(chuàng)業(yè)的學(xué)生在春假期間僅憑成本分析表就籌集了數(shù)百萬美元的資金來啟動其業(yè)余項目,。

其中一些新的人工智能初創(chuàng)公司甚至幾乎沒有一以貫之的產(chǎn)品或計劃,,或者由對底層技術(shù)缺乏真正理解的創(chuàng)始人領(lǐng)導(dǎo),他們只是在進行無厘頭炒作——但這顯然并不妨礙他們籌集數(shù)百萬美元的資金,。雖然其中一些初創(chuàng)公司最終可能會成為下一代人工智能研發(fā)的基石,,但許多公司(如果不是大多數(shù)的話)將以失敗告終。

這些過度現(xiàn)象并不僅僅局限于初創(chuàng)公司領(lǐng)域,。許多公開上市的人工智能公司,,例如湯姆·希貝爾的C3.ai公司也出現(xiàn)了上述情況。盡管該公司基本的業(yè)務(wù)表現(xiàn)和財務(wù)預(yù)測幾乎沒有變化,,但自今年年初以來,,其股價已經(jīng)翻了兩番,導(dǎo)致一些分析師警告稱,,這是一個“即將破裂的泡沫”,。

今年人工智能商業(yè)熱潮的關(guān)鍵驅(qū)動力是ChatGPT,其母公司OpenAI幾個月前從微軟(Microsoft)獲得了100億美元的投資,。微軟和OpenAI的關(guān)系源遠流長,,可以追溯到微軟Github部門和OpenAI之間的合作。Github部門和OpenAI聯(lián)手在2021年研發(fā)出了Github編碼助手,。這款編程助手基于當(dāng)時鮮為人知的OpenAI模型Codex,,很可能是根據(jù)Github上的大量代碼進行訓(xùn)練的。盡管有缺陷,,但也許正是這個早期原型幫助說服了這些精明的商業(yè)領(lǐng)袖盡早押注人工智能,,因為許多人認為這是一個“千載難逢的機會”,能夠獲得巨大的利潤,。

上述案例并不是說所有的人工智能投資都是過度的,。事實上,在我們調(diào)查的首席執(zhí)行官中,,有71%的人認為他們的企業(yè)在人工智能方面投資不足,。但我們必須提出這樣一個問題:在一個可能過度飽和的領(lǐng)域,牟取暴利者進行的無厘頭炒作是否會排擠真正的創(chuàng)新企業(yè),。

擁有極強好奇心的創(chuàng)造者:知識前沿的創(chuàng)新

人工智能創(chuàng)新不僅發(fā)生在許多初創(chuàng)公司,,而且在規(guī)模較大的《財富》美國500強企業(yè)中也很普遍,。正如我們廣為記錄的那樣,許多商業(yè)領(lǐng)袖都積極地將人工智能的特定應(yīng)用整合到他們的公司中,,但也充分考慮了公司的實際情況,。

鑒于最近的技術(shù)進步,毫無疑問,,人工智能發(fā)展進入充滿希望的時期,,而且這一時期也是獨有的。最近人工智能的飛速發(fā)展,,特別是大型語言模型,,可以歸因于其底層技術(shù)規(guī)模的擴大和相關(guān)能力的提高:可供模型和算法進行訓(xùn)練的數(shù)據(jù)規(guī)模,模型和算法本身的能力,,以及模型和算法所依賴的計算硬件的能力,。

然而,基礎(chǔ)人工智能技術(shù)的指數(shù)級增長不太可能永遠持續(xù)下去,。許多人以自動駕駛汽車為例,,認為這是人工智能的第一個大賭注,預(yù)示著其未來的發(fā)展路徑:通過達成容易實現(xiàn)的目標,,取得驚人的早期進展,,從而引發(fā)狂熱,但在面對最嚴峻的挑戰(zhàn)時,,進展會急劇放緩,,比如微調(diào)自動駕駛儀出現(xiàn)的故障,,以避免發(fā)生致命碰撞,。這就像芝諾悖論(Zeno’s paradox)所暗示的那樣,因為最后一英里往往是最難完成的,。就自動駕駛汽車而言,,盡管我們一直在朝著安全的自動駕駛汽車的目標邁進,而且似乎已經(jīng)部分實現(xiàn)了目標,,但這項技術(shù)是否以及何時能夠真正實現(xiàn),,誰也說不準。

此外,,關(guān)注人工智能的技術(shù)限制(可以做什么和不能做什么)仍然很重要,。由于大型語言模型是在龐大的數(shù)據(jù)集上訓(xùn)練出來的,因此可以有效地總結(jié)和傳播事實性知識,,并實現(xiàn)非常高效的搜索和發(fā)現(xiàn),。然而,就人工智能是否能夠?qū)崿F(xiàn)科學(xué)家,、企業(yè)家,、創(chuàng)意人士和其他典型的原創(chuàng)性工作者所可以實現(xiàn)的大膽推理飛躍而言,其應(yīng)用可能會受到更多的限制,因為它本質(zhì)上無法復(fù)制人類的情感,、同理心和靈感,,而這正是人類創(chuàng)造力的驅(qū)動力。

雖然這些擁有極強好奇心的創(chuàng)造者專注于尋找人工智能的積極應(yīng)用,,但他們可能會像羅伯特·奧本海默一樣一無所知,,視野很狹窄,只專注于解決問題(在原子彈爆炸前),。

“從技術(shù)層面講,,當(dāng)你看到某種事物能夠帶來豐碩成果,你就會繼續(xù)研究下去,,直到在技術(shù)上取得成功后,,你才會爭論應(yīng)該怎么處理它。這就是原子彈的研發(fā)情況,?!边@位原子彈之父在1954年警告說,他對自己的發(fā)明所帶來的恐怖感到內(nèi)疚,,并成為了一名反原子彈活動家,。

危言聳聽的激進分子:倡導(dǎo)單邊規(guī)則

一些危言聳聽的激進分子,尤其是經(jīng)驗豐富的,,甚至是具有強烈實用主義傾向的,、對人工智能不再抱幻想的技術(shù)先驅(qū),大聲警告人工智能的各種危險,,從社會影響和對人類的威脅,,到商業(yè)模式并不可行和估值虛高——許多人主張對人工智能進行嚴格限制,以遏制這些危險,。

例如,,人工智能先驅(qū)杰弗里·辛頓就對人工智能帶來的“生存威脅”發(fā)出了警告,他表示前景并不樂觀:“很難找到方法來阻止有邪惡目的的人利用它做壞事,?!绷硪晃患夹g(shù)專家、Facebook早期的融資支持者羅杰·麥克納米在首席執(zhí)行官峰會上警告道,,生成式人工智能的單位經(jīng)濟效益非常糟糕,,沒有哪家燒錢的人工智能公司擁有可持續(xù)的商業(yè)模式。

麥克納米說:“危害顯而易見,,有隱私問題,,有版權(quán)問題,有虛假信息問題……一場人工智能軍備競賽正在進行,,以實現(xiàn)壟斷,,從而可以控制公眾和企業(yè),。”

也許最引人注目的是,,OpenAI的首席執(zhí)行官薩姆·奧爾特曼和其他來自谷歌(Google),、微軟和其他人工智能領(lǐng)軍者的人工智能技術(shù)專家最近發(fā)表了一封公開信,警告說,,人工智能給人類帶來的滅絕風(fēng)險達到核戰(zhàn)爭一樣的層級,,并認為“減輕人工智能帶來的滅絕風(fēng)險應(yīng)該與其他類似社會規(guī)模的風(fēng)險(比如流行病和核戰(zhàn)爭)一起成為全球優(yōu)先事項?!?/p>

然而,,很難辨別這些行業(yè)的危言聳聽者是出于對人類威脅的真實預(yù)期還是出于其他動機。關(guān)于人工智能如何構(gòu)成生存威脅的猜測是一種極其有效的吸引注意力的方式,,這或許是巧合,。根據(jù)我們自己的經(jīng)驗,在最近的首席執(zhí)行官峰會上,,媒體大肆宣揚首席執(zhí)行官對人工智能的危言聳聽,,遠遠蓋過了我們對首席執(zhí)行官如何將人工智能整合到業(yè)務(wù)中的更細致的了解。散播人工智能的危言聳聽也恰好是一種有效的方式,,能夠?qū)θ斯ぶ悄艿臐撛谀芰M行炒作——從而增加投資,,并吸引投資者的興趣。

奧爾特曼已經(jīng)非常有效地引起了公眾對OpenAI正在做的事情的興趣,。最顯而易見的是,,盡管付出了巨大的經(jīng)濟損失,但他最初還是讓公眾免費,、不受限制地訪問ChatGPT,。與此同時,他對OpenAI讓用戶訪問ChatGPT的軟件中存在的安全漏洞風(fēng)險的解釋純屬隔靴搔癢,,一副事不關(guān)己的樣子,,引起了人們對行業(yè)危言聳聽者是否言行一致的質(zhì)疑。

全球治理者:通過推出指導(dǎo)方針來實現(xiàn)平衡

全球治理者對人工智能的態(tài)度不像那些危言聳聽的激進人士那樣尖銳(但同樣謹慎),,他們認為,對人工智能實施單邊限制是不夠的,,而且對國家安全有害,。相反,他們呼吁構(gòu)建可以實現(xiàn)平衡的國際競爭環(huán)境,。他們意識到,,除非達成類似于《不擴散核武器條約》的全球協(xié)議,否則敵對國家就能夠繼續(xù)沿著危險的路徑開發(fā)人工智能,。

在我們的活動上,,參議員理查德·布盧門撒爾,、前議長南希·佩洛西,、代表硅谷選區(qū)的國會議員羅·康納和其他美國國會的領(lǐng)導(dǎo)者強調(diào)了提供立法和保障措施(為人工智能安護欄)的重要性,,以鼓勵創(chuàng)新,同時避免造成大規(guī)模的社會危害,。一些人以航空監(jiān)管為例,,有兩個不同的機構(gòu)監(jiān)督飛行安全:美國聯(lián)邦航空管理局(FAA)制定規(guī)則,但美國國家運輸安全委員會(NTSB)負責(zé)查明事實,,這是兩項截然不同的工作,。規(guī)則制定者必須做出權(quán)衡和妥協(xié),而事實調(diào)查者則必須堅持不懈追求真相,,而且不能做出任何妥協(xié),。考慮到人工智能可能會加劇不可靠信息在復(fù)雜系統(tǒng)中的擴散,,監(jiān)管事實調(diào)查可能與規(guī)則制定一樣重要,,甚至更為重要。

同樣,,著名經(jīng)濟學(xué)家勞倫斯·薩默斯和傳記作家,、媒體巨頭沃爾特·艾薩克森等全球治理者都告訴我們,他們主要擔(dān)心的是,,人們沒有做好準備應(yīng)對人工智能帶來的變革,。他們認為,過去社會上最具話語權(quán),、最具影響力的精英員工,,將出現(xiàn)歷史性的勞動力中斷問題。

沃爾特·艾薩克森認為,,人工智能將對專業(yè)的“知識工作者”產(chǎn)生最大影響,,甚至能夠取代他們?!爸R工作者”對深奧知識的壟斷現(xiàn)在將受到生成式人工智能的挑戰(zhàn),,因為人工智能可以機械重復(fù)甚至是最晦澀難懂的事實,遠遠超出任何人的死記硬背和回憶能力——盡管與此同時,,艾薩克森指出,,以前的技術(shù)創(chuàng)新增加了而不是減少了人類的就業(yè)機會。同樣,,麻省理工學(xué)院(MIT)的著名經(jīng)濟學(xué)家達龍·阿西莫格魯擔(dān)心,,人工智能可能會壓低員工的工資,加劇不平等現(xiàn)象,。對這些治理者來說,,人工智能將奴役人類或?qū)⑷祟愅葡驕缃^的說法是荒謬的——這導(dǎo)致人們分散注意力,,沒有關(guān)注人工智能真正可能帶來的社會成本,這種后果是難以接受的,。

即便是一些對政府直接監(jiān)管持懷疑態(tài)度的治理者,,也更愿意看到護欄落實到位(盡管是由私營部門實施的)。例如,,埃里克·施密特認為,,政府目前缺乏監(jiān)管人工智能的專業(yè)知識,應(yīng)該讓科技公司進行自我監(jiān)管,。然而,,這種自我監(jiān)管讓人想起了鍍金時代(Gilded Age)的行業(yè)監(jiān)管俘獲,當(dāng)時的美國州際商務(wù)委員會(Interstate Commerce Commission),、美國聯(lián)邦通信委員會(The Federal Communication Commission)和美國民用航空委員會(Civil Aeronautics Board)經(jīng)常將旨在維護公共利益的監(jiān)管向行業(yè)巨頭傾斜,,這些巨頭阻止了新的競爭性創(chuàng)業(yè)者進入,保護老牌企業(yè)免受美國電話電報公司(ATT)的創(chuàng)始人西奧多·韋爾所稱的“破壞性競爭”,。

其他治理者指出,,人工智能可能會帶來一些問題,單靠監(jiān)管是無法解決的,。比如,,他們指出,人工智能系統(tǒng)可能會欺騙人們,,讓人們認為它們能夠提供可靠事實,,以至于許多人可能會放棄通過查證來確定哪些事實是可信的(忽略自身的責(zé)任),從而完全依賴人工智能系統(tǒng)——即使人工智能的應(yīng)用已經(jīng)造成了傷亡,,例如在自動駕駛汽車造成的車禍中,,或者在醫(yī)療事故中(由于粗心大意)。

這五大思想流派傳遞出來的信息更多地揭示了專家們自己的先入之見和偏見,,而不是潛在的人工智能技術(shù)本身,。盡管如此,在人工智能的喧囂中,,這是值得研究這五大思想流派,,以獲得真正的智慧和洞察力。(財富中文網(wǎng))

杰弗里·索南費爾德(Jeffrey Sonnenfeld)是耶魯大學(xué)管理學(xué)院(Yale School of Management)萊斯特·克朗管理實踐教授和高級副院長,。他被《Poets & Quants》雜志評為“年度最佳管理學(xué)教授”,。

保羅·羅默(Paul Romer)是波士頓學(xué)院(Boston College)校級教授,也是2018年諾貝爾經(jīng)濟學(xué)獎得主,。

德克·伯格曼(Dirk Bergemann)是耶魯大學(xué)(Yale University)坎貝爾經(jīng)濟學(xué)教授,兼任計算機科學(xué)教授和金融學(xué)教授,。他是耶魯大學(xué)算法,、數(shù)據(jù)和市場設(shè)計中心(Yale Center for Algorithm, Data, and Market Design)的創(chuàng)始主任,。

史蒂文·田(Steven Tian)是耶魯大學(xué)首席執(zhí)行官領(lǐng)導(dǎo)力研究所(Yale Chief Executive Leadership Institute)的研究主任,曾經(jīng)是洛克菲勒家族辦公室(Rockefeller Family Office)的量化投資分析師,。

Fortune.com上發(fā)表的評論文章中表達的觀點,,僅代表作者本人的觀點,不代表《財富》雜志的觀點和立場,。

譯者:中慧言-王芳

僅僅在今年5月,,《華爾街日報》(The Wall Street Journal)和《紐約時報》(New York Times)就分別發(fā)表了200多篇令人窒息的文章,要么宣布人類將面臨悲慘的災(zāi)難性結(jié)局,,要么宣布人類將獲得救贖,,這取決于所引用的專家的偏見和經(jīng)驗。

我們親身體會到圍繞人工智能的公共話語是多么聳人聽聞,。今年6月下旬舉行的第134屆首席執(zhí)行官峰會聚集了200多位來自大型公司的首席執(zhí)行官,,圍繞峰會的大量媒體報道捕捉到這些危言聳聽,其中,,42%的首席執(zhí)行官表示人工智能有可能在十年內(nèi)摧毀人類(這些首席執(zhí)行官們表達了很多有細微差別的觀點,,正如我們之前所捕捉到的那樣)。

今年夏天,,在商業(yè),、政府、學(xué)術(shù)界,、媒體,、技術(shù)和公民社會對人工智能的不同看法中,這些專家經(jīng)常各執(zhí)一詞,。

大多數(shù)人工智能專家的觀點往往分為五大不同的類別:欣喜若狂的忠實信徒,、牟取暴利者、擁有極強好奇心的創(chuàng)造者,、危言聳聽的激進分子,,以及全球治理者。

欣喜若狂的忠實信徒:通過人工智能系統(tǒng)獲得救贖

人們長期預(yù)測的機器自學(xué)時刻,,與人工智能70年來漸進式發(fā)展的現(xiàn)實截然不同,。在這樣的炒作中,很難知道如今到底有多大的機會,,以及哪些過于樂觀的預(yù)測會演變成幻想,。

通常,那些在人工智能前沿領(lǐng)域工作時間最長的人持有更樂觀的看法,,他們一生都致力于人類知識前沿領(lǐng)域的最新研究,。這些人工智能先驅(qū)是“忠實信徒”,他們相信自己的技術(shù)具有顛覆性潛力,,而且在很少有人接受一項新興技術(shù)的潛力和前景時,,他們就接受了這一點——并且遠遠早于這項技術(shù)進入主流,,因此,很難指責(zé)這些“忠實信徒”,。

對其中的一些人來說,,例如“人工智能教父”和Meta公司的首席人工智能科學(xué)家楊立昆(Yann LeCun),“毫無疑問,,機器最終會超越人類,。”與此同時,,楊立昆等人認為人工智能可能對人類構(gòu)成嚴重威脅的想法“荒謬至極”,。同樣,風(fēng)險投資家馬克·安德森對此不以為然,,輕易推倒了有關(guān)人工智能的“散布恐懼和末日論的高墻”,,認為人們應(yīng)該停止擔(dān)憂,“研發(fā),、研發(fā),、再研發(fā)”。

但是,,一意孤行,、過于樂觀可能會導(dǎo)致這些專家高估他們的技術(shù)能夠帶來的影響(也許是有意為之,但稍后會詳細說明),,并忽視其潛在的弊端和運營挑戰(zhàn),。

事實上,當(dāng)我們就生成式人工智能“是否會比之前的重大技術(shù)進步,,比如互聯(lián)網(wǎng),、汽車、飛機,、制冷等的發(fā)明更具變革性”對首席執(zhí)行官們進行調(diào)查時,,大多數(shù)人回答“不會”,這表明人工智能是否會像一些永恒的樂觀主義者希望我們相信的那樣,,真正顛覆社會,,仍然存在不確定性(在很大范圍內(nèi))。

畢竟,,存在真正改變社會的技術(shù)進步,,但大多數(shù)在最初的炒作之后以失敗告終。僅僅18個月前,,許多狂熱者確信加密貨幣將改變我們的日常生活——在FTX破產(chǎn),、加密貨幣大亨薩姆·班克曼-弗里德被捕(從而名譽掃地),以及“加密貨幣的冬天”來臨之前。

牟取暴利者:進行無厘頭炒作

在過去的六個月里,,在參加貿(mào)易展,、加入專業(yè)協(xié)會或接受新產(chǎn)品推介時,,毫無疑問會被聊天機器人的推銷所轟炸,。在ChatGPT推出的刺激下,圍繞人工智能的熱潮逐漸升溫,,渴望賺錢的企業(yè)家(是機會主義者,,但也很務(wù)實)紛紛涌入這一領(lǐng)域。

令人驚訝的是,,今年前五個月投入到生成式人工智能初創(chuàng)公司的資金比以往任何一年加起來都多,,僅在過去五個月中就有超過一半的生成式人工智能初創(chuàng)公司成立,而今年生成式人工智能的估值中位數(shù)比去年翻了一番,。

也許讓人想起在互聯(lián)網(wǎng)泡沫時期,,那些希望立即提升股價的公司在其名稱中添加“.com”的日子,如今,,一夜之間,,大學(xué)生創(chuàng)辦的以人工智能為重點的初創(chuàng)公司如雨后春筍般涌現(xiàn),這些初創(chuàng)公司的產(chǎn)品大都雷同,,一些創(chuàng)業(yè)的學(xué)生在春假期間僅憑成本分析表就籌集了數(shù)百萬美元的資金來啟動其業(yè)余項目,。

其中一些新的人工智能初創(chuàng)公司甚至幾乎沒有一以貫之的產(chǎn)品或計劃,或者由對底層技術(shù)缺乏真正理解的創(chuàng)始人領(lǐng)導(dǎo),,他們只是在進行無厘頭炒作——但這顯然并不妨礙他們籌集數(shù)百萬美元的資金,。雖然其中一些初創(chuàng)公司最終可能會成為下一代人工智能研發(fā)的基石,但許多公司(如果不是大多數(shù)的話)將以失敗告終,。

這些過度現(xiàn)象并不僅僅局限于初創(chuàng)公司領(lǐng)域,。許多公開上市的人工智能公司,例如湯姆·希貝爾的C3.ai公司也出現(xiàn)了上述情況,。盡管該公司基本的業(yè)務(wù)表現(xiàn)和財務(wù)預(yù)測幾乎沒有變化,,但自今年年初以來,其股價已經(jīng)翻了兩番,,導(dǎo)致一些分析師警告稱,,這是一個“即將破裂的泡沫”。

今年人工智能商業(yè)熱潮的關(guān)鍵驅(qū)動力是ChatGPT,,其母公司OpenAI幾個月前從微軟(Microsoft)獲得了100億美元的投資,。微軟和OpenAI的關(guān)系源遠流長,可以追溯到微軟Github部門和OpenAI之間的合作,。Github部門和OpenAI聯(lián)手在2021年研發(fā)出了Github編碼助手,。這款編程助手基于當(dāng)時鮮為人知的OpenAI模型Codex,很可能是根據(jù)Github上的大量代碼進行訓(xùn)練的。盡管有缺陷,,但也許正是這個早期原型幫助說服了這些精明的商業(yè)領(lǐng)袖盡早押注人工智能,,因為許多人認為這是一個“千載難逢的機會”,能夠獲得巨大的利潤,。

上述案例并不是說所有的人工智能投資都是過度的,。事實上,在我們調(diào)查的首席執(zhí)行官中,,有71%的人認為他們的企業(yè)在人工智能方面投資不足,。但我們必須提出這樣一個問題:在一個可能過度飽和的領(lǐng)域,牟取暴利者進行的無厘頭炒作是否會排擠真正的創(chuàng)新企業(yè),。

擁有極強好奇心的創(chuàng)造者:知識前沿的創(chuàng)新

人工智能創(chuàng)新不僅發(fā)生在許多初創(chuàng)公司,,而且在規(guī)模較大的《財富》美國500強企業(yè)中也很普遍。正如我們廣為記錄的那樣,,許多商業(yè)領(lǐng)袖都積極地將人工智能的特定應(yīng)用整合到他們的公司中,,但也充分考慮了公司的實際情況。

鑒于最近的技術(shù)進步,,毫無疑問,,人工智能發(fā)展進入充滿希望的時期,而且這一時期也是獨有的,。最近人工智能的飛速發(fā)展,,特別是大型語言模型,可以歸因于其底層技術(shù)規(guī)模的擴大和相關(guān)能力的提高:可供模型和算法進行訓(xùn)練的數(shù)據(jù)規(guī)模,,模型和算法本身的能力,,以及模型和算法所依賴的計算硬件的能力。

然而,,基礎(chǔ)人工智能技術(shù)的指數(shù)級增長不太可能永遠持續(xù)下去,。許多人以自動駕駛汽車為例,認為這是人工智能的第一個大賭注,,預(yù)示著其未來的發(fā)展路徑:通過達成容易實現(xiàn)的目標,,取得驚人的早期進展,從而引發(fā)狂熱,,但在面對最嚴峻的挑戰(zhàn)時,,進展會急劇放緩,比如微調(diào)自動駕駛儀出現(xiàn)的故障,,以避免發(fā)生致命碰撞,。這就像芝諾悖論(Zeno’s paradox)所暗示的那樣,因為最后一英里往往是最難完成的,。就自動駕駛汽車而言,,盡管我們一直在朝著安全的自動駕駛汽車的目標邁進,,而且似乎已經(jīng)部分實現(xiàn)了目標,但這項技術(shù)是否以及何時能夠真正實現(xiàn),,誰也說不準,。

此外,關(guān)注人工智能的技術(shù)限制(可以做什么和不能做什么)仍然很重要,。由于大型語言模型是在龐大的數(shù)據(jù)集上訓(xùn)練出來的,,因此可以有效地總結(jié)和傳播事實性知識,并實現(xiàn)非常高效的搜索和發(fā)現(xiàn),。然而,,就人工智能是否能夠?qū)崿F(xiàn)科學(xué)家、企業(yè)家,、創(chuàng)意人士和其他典型的原創(chuàng)性工作者所可以實現(xiàn)的大膽推理飛躍而言,其應(yīng)用可能會受到更多的限制,,因為它本質(zhì)上無法復(fù)制人類的情感,、同理心和靈感,而這正是人類創(chuàng)造力的驅(qū)動力,。

雖然這些擁有極強好奇心的創(chuàng)造者專注于尋找人工智能的積極應(yīng)用,,但他們可能會像羅伯特·奧本海默一樣一無所知,視野很狹窄,,只專注于解決問題(在原子彈爆炸前),。

“從技術(shù)層面講,當(dāng)你看到某種事物能夠帶來豐碩成果,,你就會繼續(xù)研究下去,,直到在技術(shù)上取得成功后,你才會爭論應(yīng)該怎么處理它,。這就是原子彈的研發(fā)情況,。”這位原子彈之父在1954年警告說,,他對自己的發(fā)明所帶來的恐怖感到內(nèi)疚,,并成為了一名反原子彈活動家。

危言聳聽的激進分子:倡導(dǎo)單邊規(guī)則

一些危言聳聽的激進分子,,尤其是經(jīng)驗豐富的,,甚至是具有強烈實用主義傾向的、對人工智能不再抱幻想的技術(shù)先驅(qū),,大聲警告人工智能的各種危險,,從社會影響和對人類的威脅,到商業(yè)模式并不可行和估值虛高——許多人主張對人工智能進行嚴格限制,,以遏制這些危險,。

例如,,人工智能先驅(qū)杰弗里·辛頓就對人工智能帶來的“生存威脅”發(fā)出了警告,他表示前景并不樂觀:“很難找到方法來阻止有邪惡目的的人利用它做壞事,?!绷硪晃患夹g(shù)專家、Facebook早期的融資支持者羅杰·麥克納米在首席執(zhí)行官峰會上警告道,,生成式人工智能的單位經(jīng)濟效益非常糟糕,,沒有哪家燒錢的人工智能公司擁有可持續(xù)的商業(yè)模式。

麥克納米說:“危害顯而易見,,有隱私問題,,有版權(quán)問題,有虛假信息問題……一場人工智能軍備競賽正在進行,,以實現(xiàn)壟斷,,從而可以控制公眾和企業(yè)?!?/p>

也許最引人注目的是,,OpenAI的首席執(zhí)行官薩姆·奧爾特曼和其他來自谷歌(Google)、微軟和其他人工智能領(lǐng)軍者的人工智能技術(shù)專家最近發(fā)表了一封公開信,,警告說,,人工智能給人類帶來的滅絕風(fēng)險達到核戰(zhàn)爭一樣的層級,并認為“減輕人工智能帶來的滅絕風(fēng)險應(yīng)該與其他類似社會規(guī)模的風(fēng)險(比如流行病和核戰(zhàn)爭)一起成為全球優(yōu)先事項,?!?/p>

然而,很難辨別這些行業(yè)的危言聳聽者是出于對人類威脅的真實預(yù)期還是出于其他動機,。關(guān)于人工智能如何構(gòu)成生存威脅的猜測是一種極其有效的吸引注意力的方式,,這或許是巧合。根據(jù)我們自己的經(jīng)驗,,在最近的首席執(zhí)行官峰會上,,媒體大肆宣揚首席執(zhí)行官對人工智能的危言聳聽,遠遠蓋過了我們對首席執(zhí)行官如何將人工智能整合到業(yè)務(wù)中的更細致的了解,。散播人工智能的危言聳聽也恰好是一種有效的方式,,能夠?qū)θ斯ぶ悄艿臐撛谀芰M行炒作——從而增加投資,并吸引投資者的興趣,。

奧爾特曼已經(jīng)非常有效地引起了公眾對OpenAI正在做的事情的興趣,。最顯而易見的是,盡管付出了巨大的經(jīng)濟損失,,但他最初還是讓公眾免費,、不受限制地訪問ChatGPT。與此同時,,他對OpenAI讓用戶訪問ChatGPT的軟件中存在的安全漏洞風(fēng)險的解釋純屬隔靴搔癢,,一副事不關(guān)己的樣子,,引起了人們對行業(yè)危言聳聽者是否言行一致的質(zhì)疑。

全球治理者:通過推出指導(dǎo)方針來實現(xiàn)平衡

全球治理者對人工智能的態(tài)度不像那些危言聳聽的激進人士那樣尖銳(但同樣謹慎),,他們認為,,對人工智能實施單邊限制是不夠的,而且對國家安全有害,。相反,,他們呼吁構(gòu)建可以實現(xiàn)平衡的國際競爭環(huán)境。他們意識到,,除非達成類似于《不擴散核武器條約》的全球協(xié)議,,否則敵對國家就能夠繼續(xù)沿著危險的路徑開發(fā)人工智能。

在我們的活動上,,參議員理查德·布盧門撒爾,、前議長南希·佩洛西,、代表硅谷選區(qū)的國會議員羅·康納和其他美國國會的領(lǐng)導(dǎo)者強調(diào)了提供立法和保障措施(為人工智能安護欄)的重要性,,以鼓勵創(chuàng)新,同時避免造成大規(guī)模的社會危害,。一些人以航空監(jiān)管為例,有兩個不同的機構(gòu)監(jiān)督飛行安全:美國聯(lián)邦航空管理局(FAA)制定規(guī)則,,但美國國家運輸安全委員會(NTSB)負責(zé)查明事實,,這是兩項截然不同的工作。規(guī)則制定者必須做出權(quán)衡和妥協(xié),,而事實調(diào)查者則必須堅持不懈追求真相,,而且不能做出任何妥協(xié)??紤]到人工智能可能會加劇不可靠信息在復(fù)雜系統(tǒng)中的擴散,,監(jiān)管事實調(diào)查可能與規(guī)則制定一樣重要,甚至更為重要,。

同樣,,著名經(jīng)濟學(xué)家勞倫斯·薩默斯和傳記作家、媒體巨頭沃爾特·艾薩克森等全球治理者都告訴我們,,他們主要擔(dān)心的是,,人們沒有做好準備應(yīng)對人工智能帶來的變革。他們認為,,過去社會上最具話語權(quán),、最具影響力的精英員工,將出現(xiàn)歷史性的勞動力中斷問題,。

沃爾特·艾薩克森認為,,人工智能將對專業(yè)的“知識工作者”產(chǎn)生最大影響,,甚至能夠取代他們?!爸R工作者”對深奧知識的壟斷現(xiàn)在將受到生成式人工智能的挑戰(zhàn),,因為人工智能可以機械重復(fù)甚至是最晦澀難懂的事實,遠遠超出任何人的死記硬背和回憶能力——盡管與此同時,,艾薩克森指出,,以前的技術(shù)創(chuàng)新增加了而不是減少了人類的就業(yè)機會。同樣,,麻省理工學(xué)院(MIT)的著名經(jīng)濟學(xué)家達龍·阿西莫格魯擔(dān)心,,人工智能可能會壓低員工的工資,加劇不平等現(xiàn)象,。對這些治理者來說,,人工智能將奴役人類或?qū)⑷祟愅葡驕缃^的說法是荒謬的——這導(dǎo)致人們分散注意力,沒有關(guān)注人工智能真正可能帶來的社會成本,,這種后果是難以接受的,。

即便是一些對政府直接監(jiān)管持懷疑態(tài)度的治理者,也更愿意看到護欄落實到位(盡管是由私營部門實施的),。例如,,埃里克·施密特認為,政府目前缺乏監(jiān)管人工智能的專業(yè)知識,,應(yīng)該讓科技公司進行自我監(jiān)管,。然而,這種自我監(jiān)管讓人想起了鍍金時代(Gilded Age)的行業(yè)監(jiān)管俘獲,,當(dāng)時的美國州際商務(wù)委員會(Interstate Commerce Commission),、美國聯(lián)邦通信委員會(The Federal Communication Commission)和美國民用航空委員會(Civil Aeronautics Board)經(jīng)常將旨在維護公共利益的監(jiān)管向行業(yè)巨頭傾斜,這些巨頭阻止了新的競爭性創(chuàng)業(yè)者進入,,保護老牌企業(yè)免受美國電話電報公司(ATT)的創(chuàng)始人西奧多·韋爾所稱的“破壞性競爭”,。

其他治理者指出,人工智能可能會帶來一些問題,,單靠監(jiān)管是無法解決的,。比如,他們指出,,人工智能系統(tǒng)可能會欺騙人們,,讓人們認為它們能夠提供可靠事實,以至于許多人可能會放棄通過查證來確定哪些事實是可信的(忽略自身的責(zé)任),,從而完全依賴人工智能系統(tǒng)——即使人工智能的應(yīng)用已經(jīng)造成了傷亡,,例如在自動駕駛汽車造成的車禍中,或者在醫(yī)療事故中(由于粗心大意),。

這五大思想流派傳遞出來的信息更多地揭示了專家們自己的先入之見和偏見,,而不是潛在的人工智能技術(shù)本身,。盡管如此,在人工智能的喧囂中,,這是值得研究這五大思想流派,,以獲得真正的智慧和洞察力。(財富中文網(wǎng))

杰弗里·索南費爾德(Jeffrey Sonnenfeld)是耶魯大學(xué)管理學(xué)院(Yale School of Management)萊斯特·克朗管理實踐教授和高級副院長,。他被《Poets & Quants》雜志評為“年度最佳管理學(xué)教授”,。

保羅·羅默(Paul Romer)是波士頓學(xué)院(Boston College)校級教授,也是2018年諾貝爾經(jīng)濟學(xué)獎得主,。

德克·伯格曼(Dirk Bergemann)是耶魯大學(xué)(Yale University)坎貝爾經(jīng)濟學(xué)教授,,兼任計算機科學(xué)教授和金融學(xué)教授。他是耶魯大學(xué)算法,、數(shù)據(jù)和市場設(shè)計中心(Yale Center for Algorithm, Data, and Market Design)的創(chuàng)始主任,。

史蒂文·田(Steven Tian)是耶魯大學(xué)首席執(zhí)行官領(lǐng)導(dǎo)力研究所(Yale Chief Executive Leadership Institute)的研究主任,曾經(jīng)是洛克菲勒家族辦公室(Rockefeller Family Office)的量化投資分析師,。

Fortune.com上發(fā)表的評論文章中表達的觀點,,僅代表作者本人的觀點,不代表《財富》雜志的觀點和立場,。

譯者:中慧言-王芳

In just the May, The Wall Street Journal and the New York Times each published over 200 breathless articles pronouncing either the gloomy catastrophic end to humanity or its salvation, depending on the bias and experience of the experts cited.

We know firsthand just how sensationalist the public discourse surrounding A.I. can be. Much of the ample media coverage surrounding our 134th CEO Summit in late June, which brings together over 200 major CEOs, seized upon these alarmist concerns, focusing on how 42% of CEOs said A.I. could potentially destroy humanity within a decade when the CEOs had expressed a wide variety of nuanced viewpoints as we captured previously.

Amidst the deafening cacophony of views in this summer of A.I., across the worlds of business, government, academia, media, technology, and civil society, these experts are often talking right past each other.

Most A.I. expert voices tend to fall into five distinct categories: euphoric true believers, commercial profiteers, curious creators, alarmist activists, and global governistas.

Euphoric true believers: Salvation through systems

The long-forecasted moment of self-learning of machines is dramatically different from the reality of seven decades of incrementally evolving A.I. advances. Amidst such hype, it can be hard to know just how far the opportunity now extends and where some excessively rosy forecasts devolve into fantasyland.

Often the most euphoric voices are those who have worked on the frontiers of A.I. the longest and have dedicated their lives to new discoveries at the frontiers of human knowledge. These A.I. pioneers can hardly be blamed for being “true believers” in the disruptive potential of their technology, having embraced the potential and promise of an emerging technology when few others did–and far before they entered the mainstream.

For some of these voices, such as “Godfather of A.I.” and Meta’s chief A.I. scientist Yann LeCun, there is “no question that machines would eventually outsmart people.” Simultaneously, LeCun and others wave away the idea A.I. might pose a grave threat to humanity as “preposterously ridiculous.” Similarly, venture capitalist Marc Andreesen dismissively and breezily swatted away the “wall of fear-mongering and doomerism” about A.I., arguing that people should just stop worrying and “build, build, build.”

But single-minded, overarching conceptual euphoria risks leading these experts to overestimate the impact of their own technology (perhaps intentionally so, but more on that later) and dismiss its potential downsides and operational challenges.

Indeed, when we surveyed the CEOs on whether generative A.I. “will be more transformative than previous seminal technological advancements such as the creation of the internet, the invention of the automobile and the airplane, refrigeration, etc.”, a majority answered “No,” suggesting there is still broad-based uncertainty over whether A.I. will truly disrupt society as much as some eternal optimists would have us believe.

After all, for every technological advancement which truly transforms society, there are plenty more which fizzled after much initial hype. Merely 18 months ago, many enthusiasts were certain that cryptocurrencies were going to life change as we know it–prior to the blowup of FTX, the ignominious arrest of crypto tycoon SBF, and the onset of the “crypto winter”.

Commercial profiteers: Selling unanchored hype

In the last six months, it has become nearly impossible to attend a trade show, join a professional association, or receive a new product pitch without getting drenched in chatbot pitches. As the frenzy around A.I. picked up, spurred by the release of ChatGPT, opportunistic, practical entrepreneurs eager to make a buck have poured into the space.

Amazingly, there has been more capital invested in generative A.I. startups through the first five months of this year than in all previous years combined, with over half of all generative A.I. startups established in the last five months alone, while median generative A.I. valuations have doubled this year compared to last.

Perhaps reminiscent of the days when companies looking for an instant boost in stock price sought to add .”com” to their name amidst the dot com bubble, now college students are hyping overlapping A.I.-focused startups overnight, with some entrepreneurial students raising millions of dollars as a side project over spring break with nothing more than concept sheets.

Some of these new A.I. startups barely even have coherent products or plans, or are led by founders with little genuine understanding of the underlying technology who are merely selling unanchored hype–but that is apparently no obstacle to fundraising millions of dollars. While some of these startups may eventually become the bedrock of next-generation A.I. development, many, if not most, will not make it.

These excesses are not contained to just the startup space. Many publicly listed A.I. companies such as Tom Siebel’s C3.ai have seen their stock prices quadruple since the start of the year despite little change in underlying business performance and financial projections, leading some analysts to warn of a “bubble waiting to pop.”

A key driver of the A.I. commercial craze this year has been ChatGPT, whose parent company OpenAI won a $10 billion investment from Microsoft several months back. Microsoft and OpenAI’s ties run long and deep, dating back to a partnership between the Github division of Microsoft and OpenAI, which yielded a Github coding assistant?in 2021. The coding assistant, based on a then-little-noticed OpenAI model called Codex, was likely trained on the huge amount of code available on Github. Despite its glitches, perhaps this early prototype helped convince these savvy business leaders to bet early and big on A.I. given what many see as a “once in a lifetime chance” to make huge profits.

All this is not to suggest that all A.I. investment is overwrought. In fact, 71% of the CEOs we surveyed thought their businesses are underinvesting in A.I. But we must raise the question of whether commercial profiteers selling unanchored hype may be crowding out genuine innovative enterprises in a possibly oversaturated space.

Curious creators: Innovation at the frontiers of knowledge

Not only is A.I. innovation taking place across many startups but it’s also rife within larger FORTUNE 500 companies. Many business leaders are enthusiastically but realistically integrating specific applications of A.I. into their companies, as we have extensively documented.

There is no question that this is a uniquely promising time for A.I. development, given recent technological advancements. Much of the recent leap forward for A.I., and large language models in particular, can be attributed to advances in the scale and capabilities of their underpinnings: the scale of the data available for models and algorithms to go to work on, the capabilities of the models and algorithms themselves, and the capabilities of the computing hardware that models and algorithms depend on.

However, the exponential pace of advancements in underlying A.I. technology is unlikely to continue forever. Many point to the example of autonomous vehicles, the first big A.I. bet, as a harbinger of what to expect: astonishingly rapid early progress by harvesting the lower-hanging fruit, which creates a frenzy–but then progress slows down dramatically in confronting the toughest challenges, such as fine-tuning autopilot glitches to avoid fatal crashes in the case of autonomous vehicles. It is the revenge of Zeno’s paradox, as the last mile is often the hardest. In the case of autonomous vehicles, even though it seems we are perennially halfway towards the goal of cars that drive themselves safely, it is anyone’s guess if and when the technology actually gets there.

Furthermore, it is still important to note the technical limitations to what A.I. can and cannot do. As the large language models are trained on huge datasets, they can efficiently summarize and disseminate factual knowledge and enable very efficient search-and-discover. However, in terms of whether it will allow for the bold inferential leaps which are the domain of scientists, entrepreneurs, creatives, and other exemplars of human originality, A.I.’s use may be more confined, as it is intrinsically unable to replicate the human emotion, empathy, and inspiration, which drive so much of human creativity.

While these curious creators are focused on finding positive applications of A.I., they risk being as na?ve as a pre-atomic bomb Robert Oppenheimer in their narrow focus on problem-solving.

“When you see something that is technically sweet, you go ahead, and do it and you argue about what to do about it only after you have had your technical success. That is the way it was with the atomic bomb,” the father of the atomic bomb, who was wracked by guilt over the horrors his creation unleashed and turned into an anti-bomb activist, warned in 1954.

Alarmist Activists: Advocating unilateral rules

Some alarmist activists, especially highly experienced, even pioneering disenchanted technologists with strong pragmatic anchorings, loudly warn of the dangers of A.I. for everything from the societal implications and the threat to humanity to non-viable business models and inflated valuations–and many advocate for strong restrictions on A.I. to contain these dangers.

For example, one A.I. pioneer, Geoffrey Hinton, has warned of the “existential threat” of A.I., saying ominously that “it is hard to see how you can prevent the bad actors from using it for bad things.” Another technologist, early Facebook financial backer Roger McNamee, warned at our CEO Summit that the unit economics of generative A.I. are terrible and that no cash-burning A.I. company has a sustainable business model.

“The harms are really obvious”, said McNamee. “There are privacy issues. There are copyright issues. There are disinformation issues….an arms race is underway to get to a monopoly position, where they have control over people and businesses.”

Perhaps most prominently, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman and other A.I. technologists from Google, Microsoft, and other A.I. leaders recently issued an open letter warning that A.I. poses an extinction risk to humanity on par with nuclear war and contending that “mitigating the risk of extinction from A.I. should be a global priority alongside other societal-scale risks such as pandemics and nuclear war.”

However, it can be difficult to discern whether these industry alarmists are driven by genuine anticipation of threats to humanity or other motives. It is perhaps coincidental that speculation about how A.I. poses an existential threat is an extremely effective way to drive attention. In our own experience, media coverage trumpeting CEO alarmism on A.I. from our recent CEO Summit far overshadowed our more nuanced primer on how CEOs are actually integrating A.I. into their businesses. Trumpeting alarmism over A.I. also happens to be an effective way to generate hype over what AI is potentially capable of–and thus greater investment and interest.

Already, Altman has been very effective in generating public interest in what OpenAI is doing, most obviously by initially giving the public free, unfettered access to ChatGPT at a massive financial loss. Meanwhile, his nonchalant explanation for the dangerous security breach in the software that OpenAI used to connect people to ChatGPT raised questions over whether industry alarmists’ actions match their words.

Global governistas: Balance through guidelines

Less strident on A.I. than the alarmist activists (but no less wary), are global governistas, who view unilateral restraints being placed on A.I. would be inadequate and harmful to national security. Instead, they are calling for a balanced international playing field. They are aware that hostile nations can continue exploiting A.I. along dangerous paths unless there are agreements akin to the global nuclear non-proliferation pacts.

These voices advocate for guidelines if not regulation around the responsible use of A.I. At our event, Senator Richard Blumenthal, Speaker Emerita Nancy Pelosi, Silicon Valley Congressman Ro Khanna, and other legislative leaders emphasized the importance of providing legislative guardrails and safeguards to encourage innovation while avoiding large-scale societal harms. Some point to the example of aviation regulation as an example to follow, with two different agencies overseeing flight safety: The FAA writes the rules, but the NTSB establishes the facts, two very different jobs. While rule writers have to make tradeoffs and compromise, fact-finders have to be relentless and uncompromising in pursuit of truth. Given how A.I. may exacerbate the proliferation of unreliable information across complex systems, regulatory fact-finding could be just as important if not even more so than rule-setting.

Similarly, there are global governistas such as renowned economist Lawrence Summers and biographer and media titan Walter Isaacson who have each told us that their major concern revolves around the lack of preparedness for changes driven by A.I. They suggest a historic workforce disruption among the formerly most vocal and powerful elite workers in society.

Walter Isaacson argues that A.I. will have the greatest displacement effect on professional “knowledge workers”, whose monopoly on esoteric knowledge will now be challenged by generative A.I. capable of regurgitating even the most obscure factoids far beyond the rote memory and recall capacity of any human being–though at the same time, Isaacson notes that previous technological innovations have enhanced rather than reduced human employment. Similarly, famous MIT economist Daron Acemoglu worries about the risk that A.I. could depress wages for workers and exacerbate inequality. For these governistas, the notion that A.I. will enslave humans or drive humans into extinction is absurd–an unwelcome distraction from the real social costs that A.I. could potentially impose.

Even some governistas who are skeptical of direct government regulation would prefer to see guardrails put in place, albeit by the private sector. For example, Eric Schmidt has argued that governments currently lack the expertise to regulate A.I. and should let the technology companies self-regulate. This self-regulation, however, harkens back to the industry-captured regulation of the Gilded Age, where the Interstate Commerce Commission, The Federal Communication Commission, and the Civil Aeronautics Board often tilted regulation intended to be in the public interest towards industry giants, which blocked new rival startup entrants protecting established players from what ATT founder Theodore Vail labeled as “destructive competition.”

Other governistas point out that there are problems potentially created by A.I. that cannot be solved through regulation alone. For example, they point out that A.I. systems can fool people into thinking that they can reliably offer up facts to the point where many may abdicate their individual responsibility for paying attention to what is trustworthy, and thus rely totally on A.I. systems–even when versions of AI already kill people, such as in autopilot-driven car crashes, or in careless medical malpractice.

The messaging of these five tribes reveals more about the experts’ own preconceptions and biases than the underlying A.I. technology itself–but nevertheless, these five schools of thought are worth investigating for nuggets of genuine intelligence and insight amidst the artificial intelligence cacophony.

Jeffrey Sonnenfeld is the Lester Crown Professor in Management Practice and Senior Associate Dean at Yale School of Management. He was named “Management Professor of the Year” by Poets & Quants magazine.

Paul Romer, University Professor at Boston College, was a co-recipient of the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 2018.

Dirk Bergemann is the Campbell Professor of Economics at Yale University with secondary appointments as Professor of Computer Science and Professor of Finance. He is the Founding Director of the Yale Center for Algorithm, Data, and Market Design.

Steven Tian is the director of research at the Yale Chief Executive Leadership Institute and a former quantitative investment analyst with the Rockefeller Family Office.

The opinions expressed in Fortune.com commentary pieces are solely the views of their authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions and beliefs of Fortune.