本文是《財(cái)富》雜志氣候變化突破方案系列報(bào)道的一部分,,客座編輯為比爾·蓋茨,。

動(dòng)筆十多年后,比爾·蓋茨的新書《如何避免氣候?yàn)?zāi)難:我們擁有的解決方案和我們需要的突破》終于面世,?!叭绾伪苊狻蹦遣糠肿銎饋聿⒉蝗菀祝w茨計(jì)劃的明確性和緊迫性,,可能會(huì)讓數(shù)百萬讀者迅速積極響應(yīng)起來,。

《財(cái)富》雜志希望進(jìn)一步深入挖掘,探索蓋茨和其他人提出的挑戰(zhàn),。為此,,我們邀請(qǐng)這位著名的慈善家擔(dān)任2月16日當(dāng)天《財(cái)富》雜志的“客座編輯”。

本書出版之前,,《財(cái)富》雜志主編黎克騰,,跟微軟聯(lián)合創(chuàng)始人也是投資人蓋茨坐下長(zhǎng)談,,討論如何才能防止氣候變化惡化,新能源“奇跡”傳遞錯(cuò)誤信息,,以及當(dāng)前蓋茨向哪些領(lǐng)域大舉投資,。至于討論中談到了他對(duì)人造肉漢堡(以及其他一些著名投資人的少量“投資目標(biāo)”)的濃厚興趣,則是意外收獲,。

為了簡(jiǎn)潔及表述清晰,,對(duì)話經(jīng)過編輯。

比爾,你剛剛寫了避免“氣候?yàn)?zāi)難”的書,,然而現(xiàn)在地球上大多數(shù)人都在關(guān)注另一場(chǎng)災(zāi)難——新冠病毒,。你擔(dān)不擔(dān)心讀者可能沒準(zhǔn)備好同時(shí)面對(duì)兩種威脅?

先說說我為什么要寫這本書,。2008年,,在我離開微軟的幾年前,在微軟工作的一些朋友說:“比爾,,你應(yīng)該關(guān)注氣候變化問題,。”

我讀到瓦茨拉夫·斯米爾的書,,對(duì)鋼鐵,、水泥、電力等物質(zhì)經(jīng)濟(jì)產(chǎn)生了濃厚的興趣,。他讓我意識(shí)到,,人們對(duì)輕易獲取各種資源感覺理所當(dāng)然。

比如電力非??煽坑至畠r(jià),,斯米爾在書中談到電力普及方面各種令人驚嘆的工作。當(dāng)然,,這些工作也是導(dǎo)致溫室氣體排放和加劇氣候變化的因素,。所以我開始思考如何改變一切。我在想:“真能實(shí)現(xiàn)嗎,?”

當(dāng)然,,基金會(huì)在貧窮國(guó)家已經(jīng)在做各種工作,經(jīng)濟(jì)欠發(fā)達(dá)國(guó)家的建筑通常是用廢舊金屬建造,。沒有輸電線,。用水方面,一些地區(qū)的屋頂上裝有小型水箱,,因?yàn)楫?dāng)?shù)貨]有給水系統(tǒng),,即便有也極其不可靠,。

后來,朋友介紹我認(rèn)識(shí)了肯·卡爾德拉教授(卡內(nèi)基科學(xué)研究所)和大衛(wèi)·基思教授(目前在哈佛大學(xué)執(zhí)教),。我們一年開六次會(huì),。他們也會(huì)介紹其他專家參加,我們選擇某個(gè)話題,,比如儲(chǔ)存能量,、電動(dòng)汽車或煉鋼,提前閱讀大量材料,,然后討論半天,。我對(duì)相關(guān)話題非常感興趣。

我的理解框架其實(shí)不少,,2010年我在TED發(fā)表了演講(題目叫“從零開始創(chuàng)新”),,一共講了三場(chǎng)。其中一場(chǎng)關(guān)于政府預(yù)算問題在哪,,我保證總有一天這會(huì)被當(dāng)成預(yù)言,;2015年的演講關(guān)于疫病,可能是到現(xiàn)在瀏覽量最高的一場(chǎng)(編者按:該場(chǎng)有先見之明的TED演講標(biāo)題是“下一次大爆發(fā),?我們還沒有準(zhǔn)備好,。”目前瀏覽量已經(jīng)達(dá)到3900萬次,。),;關(guān)于氣候的那場(chǎng)并不長(zhǎng)。我想想,,大概15分鐘,?——可以找來看看。

那場(chǎng)演講的目的是:“困難太大,,需要?jiǎng)?chuàng)新——很多創(chuàng)新,。”盡管我現(xiàn)在比十年前知道得更多,,但那仍然是我的基本認(rèn)識(shí)框架,,也是新書的框架。

但就像現(xiàn)在一樣,,十年前你在TED上發(fā)表關(guān)于氣候變化的演講時(shí),,全世界也被另一場(chǎng)全球危機(jī)分散了注意力。

不幸的是,,2010年左右那段時(shí)間里,,也就是金融危機(jī)之后,(應(yīng)對(duì))氣候變化的能源消耗大幅下降,。然后隨著經(jīng)濟(jì)開始復(fù)蘇,,興趣稍微上升,。

對(duì)我來說,之后一個(gè)重大里程碑是2015年巴黎氣候談判之前一年,,當(dāng)時(shí)我對(duì)大家說:“為什么人們開這些會(huì)議,,卻不討論研發(fā)預(yù)算和刺激創(chuàng)新的想法?”

大概結(jié)構(gòu)是:“我們以國(guó)家身份來談?wù)劷谶M(jìn)展,?!弊罱陲L(fēng)能、太陽能發(fā)電,,以及電動(dòng)汽車應(yīng)用方面有些進(jìn)展,。并不是說這些事情很容易,但這都是最容易做到減排的手段,。

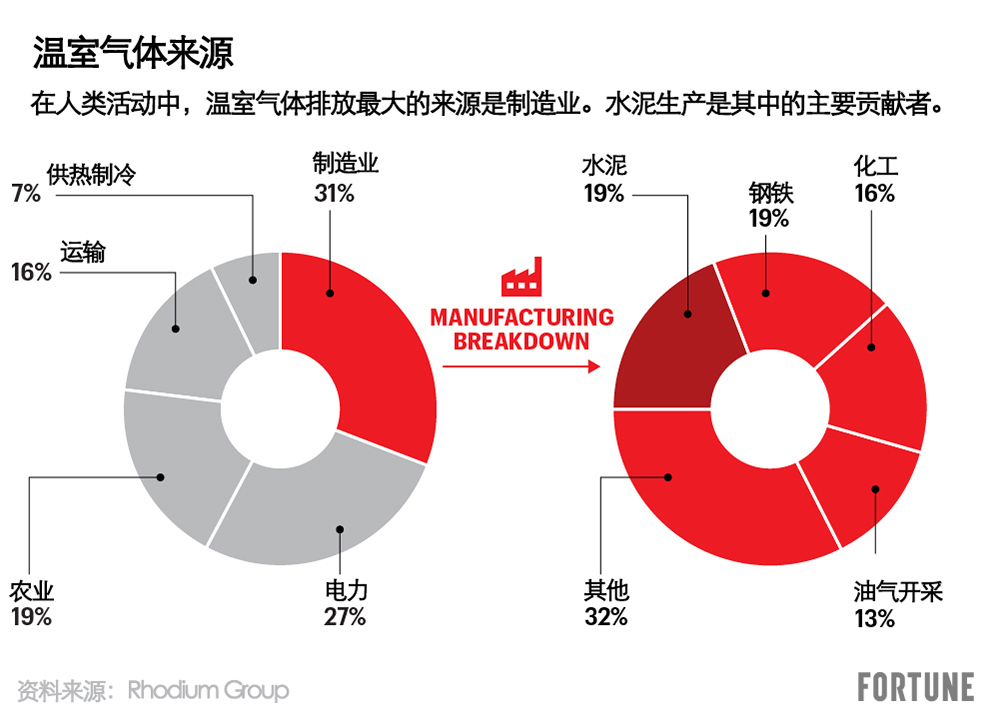

所以當(dāng)你說:“五年后或者十年后能夠做什么,?”人們并不會(huì)答:“我正用全新的方式煉鐵?!币?yàn)楦鲊?guó)煉鐵方式差別不大,。鋼鐵在全球都是具有競(jìng)爭(zhēng)力的行業(yè),。因此,,溫室氣體排放70%以上的來源從未出現(xiàn)在“讓我們討論下短期減排”的討論中。奇怪的是,,真正難推動(dòng)的領(lǐng)域幾乎沒人討論過,,占排放70%的鋼鐵、水泥或航空就是很好的例子,。

但到了2015年,在COP21(跟當(dāng)年巴黎聯(lián)合國(guó)氣候變化大會(huì)同時(shí)舉辦的可持續(xù)創(chuàng)新論壇)上,,這問題被提了出來,。

法國(guó)組織者想做一些不同的事情,他們希望(印度總理納倫德拉)莫迪能來,。莫迪并不想?yún)?huì),,然后被追問“短期減排多少?”因?yàn)橛《鹊碾娏π枨笫乾F(xiàn)在的五倍,,才可以讓大部分人口維持基本的生活方式,。所以他不會(huì)出席。

但是,,COP21的附帶結(jié)果也就是所謂的使命創(chuàng)新,,不僅關(guān)注增加能源研發(fā)預(yù)算,,還要確保有私營(yíng)部門投資者愿意承擔(dān)風(fēng)險(xiǎn),將有希望的創(chuàng)意轉(zhuǎn)化為公司,,前提是研發(fā)實(shí)驗(yàn)室將創(chuàng)意變?yōu)楝F(xiàn)實(shí),。

當(dāng)時(shí),Kleiner Perkins的約翰?多爾或維諾德?科斯拉的風(fēng)投基金做了大量綠色投資,,業(yè)績(jī)并不好,。Kleiner Perkins賭的是菲斯克(汽車)而不是特斯拉。很多太陽能電池板方面的(投資)并不順利,。所以我承諾籌錢向該領(lǐng)域投資,。

后來就成立了突破能源風(fēng)投基金,隸屬于我旗下主要關(guān)注氣候變化的機(jī)構(gòu),。公司覆蓋幾個(gè)不同的領(lǐng)域,,包括專注政策解決方案的部門。不過當(dāng)前主要是從事風(fēng)投,。

我們籌集了剛好10億多美元,,現(xiàn)在投資了50家公司,進(jìn)展很順利,。我們也找了其他人投資,。

本書出版的時(shí)候(2月16日),我們稱之為BEV2的風(fēng)投基金已經(jīng)融到數(shù)十億美元,,將繼續(xù)投50家公司,,其中大部分都會(huì)失敗。即便是成功也比典型的軟件公司更難,,因?yàn)樾枰度氪罅抠Y金,,還需要產(chǎn)業(yè)合作關(guān)系。所以這是完全不同的投資方式,,我的目標(biāo)是幫助擴(kuò)大創(chuàng)新規(guī)模,。

但是,就在你擴(kuò)大投資規(guī)模還召集其他投資者和決策者關(guān)注能源領(lǐng)域的激進(jìn)創(chuàng)新時(shí),,趕上了新冠疫情,。你似乎把注意力和慈善事業(yè)放在尋找新冠治療方法和疫苗上,去年9月你接受《財(cái)富》雜志采訪時(shí)談到過,。

這應(yīng)該夸一夸這一代的人們,,即便當(dāng)前身處疫情中,大家也還是真正關(guān)心氣候危機(jī)的,。

這次不像金融危機(jī)(2007年-2008年)期間,,當(dāng)時(shí)人們說,“現(xiàn)在情況很艱難,沒有工夫管氣候變化,?!奔幢愕?010年,如果對(duì)公眾民意調(diào)查,,也會(huì)發(fā)現(xiàn)人們對(duì)氣候的興趣已經(jīng)下降,。

而在接下來十年里,關(guān)注又逐漸增加,,遭遇疫情時(shí)我還在想:“會(huì)出現(xiàn)什么情況,?”實(shí)際上,疫情期間人們對(duì)氣候變化的關(guān)注有所上升,,這有點(diǎn)奇怪,。

看看拜登總統(tǒng)挑選的專家,,也是差不多情況,,這屆政府里,,有很多氣候問題專家,。總統(tǒng)正關(guān)注著幾個(gè)互相疊加的危機(jī),,疫情和氣候變化重要性相當(dāng),,這點(diǎn)相當(dāng)讓人贊嘆。

而且總統(tǒng)初選和大選期間,,候選人遇到的氣候問題數(shù)量比以往都要多,。再看看歐洲的復(fù)蘇計(jì)劃,資本投資也極其傾向氣候變化領(lǐng)域,。超過三分之一的資金都與此有關(guān),。

所以我感覺很幸運(yùn),在某種程度上年輕人提升了話題的重要性,。我年輕的時(shí)候都沒做到,。當(dāng)時(shí)我都沒上街游行,。

我的觀點(diǎn)是,“既然你們?nèi)绱岁P(guān)心,,而且能夠理想主義地說:‘讓我們盡一切努力在2050年之前實(shí)現(xiàn)零排放’——就應(yīng)該制定相應(yīng)的計(jì)劃,,根據(jù)計(jì)劃逆推,然后說:‘鋼鐵,、水泥和航空要怎么做?’”

不希望人們想:“哦,,我們只想確保多裝幾個(gè)太陽能電池板,?!比缓?0年過去,排放并沒有什么變化,。

所以除非計(jì)劃得當(dāng),,否則最后只會(huì)引發(fā)很多憤世嫉俗和失望。

所以你決定把計(jì)劃寫成書。

是的,新書主要說的是計(jì)劃。書中沒具體解釋為什么氣候變化有害,,但還是用一章的篇幅大概講了講,,還有一章關(guān)于適應(yīng)的。但書中大部分內(nèi)容主要還是類似于:“溫室氣體排放達(dá)510億噸,,以下列舉出排放的領(lǐng)域,。”看看各領(lǐng)域的情況,,然后說:“如果想實(shí)現(xiàn)零排放,,達(dá)到同樣產(chǎn)量成本的情況下,要貴多少,?”

這就是我說的綠色溢價(jià)指標(biāo),。我們能夠討論的是:“當(dāng)今水泥的綠色溢價(jià)是多少?哪家公司的技術(shù)能夠?qū)崿F(xiàn)減半,?有沒有可能降到零,?”

將綠色溢價(jià)降到零是很神奇的,未來十年電動(dòng)汽車將能實(shí)現(xiàn)這個(gè)目標(biāo),。也就是說,,不需要政府資助創(chuàng)新,也不需要個(gè)人資助,。只要量達(dá)到一定程度,,產(chǎn)品變得便宜,充電站也變得普及,,政客就可以參與,。

到時(shí)政客就能夠說,2035年,、2040年之前禁止燃油車,,公眾不會(huì)震驚地問:“什么?,!”

如果綠色溢價(jià)降到接近零,,相關(guān)政策的實(shí)行就成為可能,不過在大量碳排放的地區(qū)也要采取同樣措施,。有些領(lǐng)域,,比如鋼鐵或水泥生產(chǎn)實(shí)施起來都很困難。不管怎樣,,這都是最基本的,。

我非常喜歡這本書的一點(diǎn)是,讀者可以體驗(yàn)學(xué)習(xí)氣候科學(xué)的過程,。舉例來說,,你對(duì)汽油比蘇打水便宜感到驚奇,或者解釋為什么某些氣體吸收或反射太陽輻射取決于原子組成時(shí),,感覺好像你正在高興地跟讀者分享發(fā)現(xiàn),。在寫書的過程中,,你有沒有意識(shí)到要分享個(gè)人發(fā)現(xiàn)之旅?

對(duì)我來說,,所有東西都很有趣,。

當(dāng)你在其他某些地方讀到相關(guān)內(nèi)容時(shí),對(duì)內(nèi)容的解釋經(jīng)常并不清晰,,比方說,,你會(huì)讀到文章說:“減排力度相當(dāng)于10000戶或40000輛汽車?!?/p>

你得想:“我得費(fèi)勁理解數(shù)字,,總數(shù)是多少,然后算這些數(shù)字占多少,?”

我想把數(shù)字簡(jiǎn)化,,如果有人談到10000戶或40000輛汽車碳減排時(shí),我就能夠回答這個(gè)問題:“占總碳排放量的百分比是多少,?”

大多數(shù)人讀到相關(guān)文章時(shí)會(huì)說:“這些都只是胡言亂語,。”當(dāng)一開始努力理解時(shí),,能量單位都非常大,容易讓人感覺混亂,。對(duì)我來說,,能夠利用某些熟悉的事物去理解比較有吸引力。

必須承認(rèn),,這本書非常感謝肯·卡爾德拉和大衛(wèi)·基思,,他們向我傳授了很多知識(shí),還介紹了很多人,。

還有像(微軟前首席技術(shù)官)內(nèi)森·米爾沃德和(多產(chǎn)發(fā)明家)洛厄爾·伍德等人,,每當(dāng)我對(duì)物理或化學(xué)方面有疑惑時(shí),就給他們寫郵件,。當(dāng)然還有瓦茨拉夫·斯米爾,,他寫了很多書,對(duì)諸如1800年工業(yè)經(jīng)濟(jì)的概況和之后的重大突破的著迷,,為我提供了靈感,。

我很喜歡研究這些。其實(shí)很簡(jiǎn)單,。跟大多數(shù)領(lǐng)域一樣,,就這么幾個(gè)概念,但必須真正了解它們。

比如能量速率,、能源數(shù)量,,以及儲(chǔ)存時(shí)間。

對(duì)能源來說,,這些相當(dāng)于“能不能想用的時(shí)候就用,?”斯米爾做了直觀展示,,“一座城市耗能量多少,,或者一個(gè)家庭耗能量多少?”這樣腦中就能理解各種數(shù)字和常識(shí),。

為了理解,,我?guī)鹤尤ッ旱V工廠,還去了水泥廠和造紙廠實(shí)地參觀,。因?yàn)槲覀冎欢浖?,在化學(xué)實(shí)驗(yàn)方面實(shí)在不擅長(zhǎng)。

以前我想的是:“只算化學(xué)方程式就好,,別用試管實(shí)際操作,。我可能造成爆炸?!?/p>

成長(zhǎng)過程中,,我從沒有造過小火車或飛機(jī)之類的物品。所以我一直覺得:“上帝,,實(shí)體的東西才是真的,。”

我是說,,得有人真去建造機(jī)器和工廠,。

不管怎樣,學(xué)習(xí)很有趣,。如果告訴別人我花了多少時(shí)間或者讀了多少書,,就得小心點(diǎn),因?yàn)槁犉饋硐袷谴蹬J裁吹?。但我最大的?yōu)點(diǎn)就是喜歡當(dāng)學(xué)生,。

我很喜歡的說法是,只要了解得足夠多,,實(shí)際上什么事情都很簡(jiǎn)單,。我有足夠的信心,還有很聰明的朋友,,他們會(huì)幫我達(dá)到目標(biāo),,我可以說:“我要學(xué)習(xí),最終達(dá)到一切都能夠解釋通的程度,?!?/p>

在書中的某些部分,,你似乎在凝視未來。去年秋天我讀到第一版書稿中,,你提到“美國(guó)退出2015年巴黎協(xié)議”,,還說“之后美國(guó)總統(tǒng)拜登會(huì)將其逆轉(zhuǎn)”,。你早在美國(guó)總統(tǒng)大選前就能夠預(yù)測(cè)到,,真令人驚訝。

書中的大部分內(nèi)容實(shí)際上是在10個(gè)月前就完成了的,。我當(dāng)時(shí)考慮了很久,,要不要出版。

剛開始問題是,,如果特朗普連任,,顯然會(huì)影響美國(guó)按照書中呼吁行事的能力。這本書主要關(guān)于創(chuàng)新,,美國(guó)控制著當(dāng)今世界50%以上的創(chuàng)新能力,,創(chuàng)新會(huì)發(fā)生在大學(xué)里,、國(guó)家實(shí)驗(yàn)室里,還有風(fēng)險(xiǎn)投資當(dāng)中,。如果不讓美國(guó)推動(dòng)創(chuàng)新,那么全世界創(chuàng)新都會(huì)停滯,。因?yàn)樵诿绹?guó),創(chuàng)新不僅僅為了本國(guó)公民,,也為了其他人,。

如果我們可以廉價(jià)制造清潔(無碳)水泥,,30年后當(dāng)發(fā)展中國(guó)家為人民建造住房時(shí)也會(huì)選擇清潔水泥。

所以當(dāng)我寫作時(shí),,最后幾章變得非常復(fù)雜,,我不得不琢磨措辭,“如果民主黨候選人當(dāng)選……”等等,。

還有疫情來襲,,我想,“哦,,人們注意力可能有點(diǎn)分散,。”

所以在大選后,,我決定對(duì)書做點(diǎn)修訂,,也許增加一些技術(shù)進(jìn)展。大選后我對(duì)書完整檢查了一遍,,又加了些內(nèi)容,。

從第一章到第九章,幾乎沒有重大修訂,。但到了第10章至第12章,,談及政府政策等相關(guān)問題時(shí),,我做了相當(dāng)多修改,。即使民主黨控制了白宮和國(guó)會(huì)、參議院幾乎平分秋色,,而且美國(guó)已經(jīng)陷入赤字,,我們也必須拿出不需要大量資源的計(jì)劃。

這是可行的,,我相當(dāng)樂觀,。

其中涉及的政治太復(fù)雜。在第11章路線圖中,,你提出了激勵(lì)和抑制或懲罰政策措施,,也就是胡蘿卜和大棒。但過去我們看到,,棍子更難到位,。

以《平價(jià)醫(yī)療法案》為例,行政部門和國(guó)會(huì)兩院中民主黨占多數(shù),,僅僅是個(gè)人授權(quán)和相關(guān)處罰的概念就已經(jīng)導(dǎo)致立法內(nèi)戰(zhàn),,而且到如今仍在持續(xù)。

我讀到書中關(guān)于碳價(jià)格設(shè)定部分,,實(shí)際上是“碳稅”,,稅率高到能夠抵消綠色溢價(jià),我想知道你對(duì)近期實(shí)現(xiàn)的把握有多大,?正如你寫到:“為碳排放定價(jià),,是消除綠色溢價(jià)能做的關(guān)鍵事項(xiàng)之一?!?/strong>

如果沒有創(chuàng)新,,即便碳捕獲可以降到比方每噸100美元,仍然要面臨巨大挑戰(zhàn),因?yàn)槊磕晏寂欧帕坑?10億噸,。在世界上某個(gè)地方必須找到每年5萬億美元的支出,,占世界經(jīng)濟(jì)5%以上。這是不可能的,,沒機(jī)會(huì),。

當(dāng)然,從政治上征收任何形式的碳稅都非常困難,。法國(guó)試圖提高柴油價(jià)格時(shí),,人們大喊:“嘿,不能這么做,!”類似努力不可避免地被減弱,,因?yàn)閷?shí)施起來的收獲與人們的感受并不成比例。

可以嘗試進(jìn)行彌補(bǔ),,但在法國(guó)的例子中,,住在城市之外不得不開車趕路的人,覺得住在城市的精英忽視了自己,,這也是各個(gè)富裕國(guó)家普遍存在的政治現(xiàn)象,。最終法國(guó)還是廢除了柴油稅。

現(xiàn)在公眾不太愿意掏錢避免負(fù)面影響,,畢竟這些負(fù)面影響大多在遙遠(yuǎn)的未來,。我是說,確實(shí)有一些有關(guān)天氣的負(fù)面現(xiàn)象已經(jīng)顯露,,比如森林火災(zāi),,還有非常炎熱的日子。

很高興人們已經(jīng)注意到,,如果目前不采取行動(dòng),,如今的負(fù)面影響將無法與2080年和2100年的境遇相比,對(duì)生活在赤道附近的人來說更是如此,。到2100年,,夏天在印度戶外活動(dòng)將難以忍受。戶外工作根本不可能,,畢竟身體的排汗量是有限的,。

書中接近結(jié)尾的地方,你總結(jié)實(shí)現(xiàn)零排放的計(jì)劃時(shí)談到“加速創(chuàng)新需求”,。這一概念似乎對(duì)成功非常關(guān)鍵,,而且似乎跟你在慈善事業(yè)中做的很多工作也有所不同。你跟梅琳達(dá)創(chuàng)立的基金會(huì)經(jīng)常資助創(chuàng)新投資的公司,。但在一些根本不存在市場(chǎng)的地方開創(chuàng)建立需求側(cè),,是另一種挑戰(zhàn),。

例如在制藥行業(yè),制藥巨頭通過大量生物技術(shù)初創(chuàng)公司為創(chuàng)新提供市場(chǎng),,跟有希望治療某種適應(yīng)癥的實(shí)驗(yàn)候選藥物競(jìng)爭(zhēng),。氣候方面是否也有類似模式,即能源巨頭為能源初創(chuàng)企業(yè)在零排放方面的進(jìn)展提供現(xiàn)成市場(chǎng),?還是像國(guó)防工業(yè)創(chuàng)新一樣,,“市場(chǎng)”必須由政府提供?

能源方面難得多,。相比之下,,軟件反而最簡(jiǎn)單。醫(yī)學(xué)的難度介于中間,。與氣候有關(guān)的事情最困難,。

軟件方面,總有一些客戶不喜歡現(xiàn)有的軟件,,認(rèn)為應(yīng)該更簡(jiǎn)單,、更便宜,或者在某些方面功能更多,。只要能從壟斷巨頭那里搶來一小塊市場(chǎng),,就可以服務(wù)某些客戶,因?yàn)槟隳軌蚋玫貪M足需求,。軟件創(chuàng)新者面前有現(xiàn)成的市場(chǎng)。

醫(yī)藥也一樣,??纯锤鞣N各樣的疾病,也許新產(chǎn)品是口服而不是注射,,或者能夠減少一些副作用,。或者,,希望每隔一段時(shí)間找到全新的方法治療不治之癥,。但這一行業(yè)同時(shí)也要面臨各種監(jiān)管、檢查和副作用等問題,。

氣候變化方面最困難的是,,制造清潔鋼鐵除了能夠保護(hù)地球之外,并沒有額外益處,。如果僅僅是跟傳統(tǒng)上公認(rèn)的工藝略有不同,,買家很可能發(fā)出疑問:“耐用嗎,會(huì)變脆嗎,,會(huì)生銹嗎,?”

人們對(duì)任何變化都抱著懷疑態(tài)度,。因?yàn)殇撹F非常可靠,,水泥也一樣,。有個(gè)公式可以精確計(jì)算強(qiáng)度,測(cè)試本身不是為了測(cè)試特性,,只是測(cè)試是否遵循了公式,。因此,市場(chǎng)中并沒有專門一塊愿意為清潔鋼鐵或水泥支付更高價(jià)格的,。

現(xiàn)在太陽能電池板的情況是,,衛(wèi)星需要能源,太陽能電池板是唯一的方法,。哪怕不經(jīng)濟(jì),,德國(guó)和日本也買了。量不大,,但足夠啟動(dòng)學(xué)習(xí)曲線,。然后包括美國(guó)在內(nèi)其他國(guó)家實(shí)施稅收抵免,學(xué)習(xí)曲線逐漸擴(kuò)大,。

我們已經(jīng)看到學(xué)習(xí)曲線模式在風(fēng)能和鋰離子電池上的應(yīng)用,,這是算是奇跡。

可悲的是,,大多數(shù)人認(rèn)為,,“電池做得夠汽車用,就可以做得能夠讓整個(gè)電網(wǎng)都用,,我們要在電網(wǎng)創(chuàng)造另一個(gè)奇跡,。”但他們沒有意識(shí)到,,很多希望創(chuàng)造奇跡的嘗試,,比如燃料電池或氫動(dòng)力汽車都還沒有成功。

舉個(gè)例子,,在裂變動(dòng)力核反應(yīng)堆方面,,創(chuàng)新還有其他難點(diǎn)。成本和安全問題引發(fā)的擔(dān)憂非常大,,除非用全新設(shè)計(jì)重建反應(yīng)堆,,在經(jīng)濟(jì)性和安全性上徹底革新,否則前路只會(huì)是死胡同,。這就是我在(核能公司)TerraPower(蓋茨擔(dān)任董事會(huì)主席)努力做的事情,。

如果把過往的成功投射到這些領(lǐng)域,最后可能認(rèn)為事情比實(shí)際情況簡(jiǎn)單得多,。你提的問題非常好,,因?yàn)闀忻枋稣w戰(zhàn)略的一部分,,就是為清潔鋼材找買家。

假設(shè)現(xiàn)在綠色溢價(jià)是每噸100美元,。有人創(chuàng)辦一家每噸溢價(jià)僅50美元的清潔鋼鐵公司,,你會(huì)對(duì)那個(gè)人說:“干得好!”但事實(shí)上市場(chǎng)規(guī)模為零,,因?yàn)槊繃嵍喑?0美元,,只意味著成本更高。

現(xiàn)在我們要做的是努力讓資金更充裕的公司,,比如科技巨頭同意每當(dāng)建造新大樓,,就要使用20%的清潔鋼材?;貓?bào)是可以對(duì)外宣稱:“大樓用了20%的清潔鋼材,。”

所以我們得創(chuàng)造需求側(cè),。我熱愛創(chuàng)新的供給端,,要去找教授,找有瘋狂創(chuàng)意的人,。所以突破能源投資公司有很多類似的項(xiàng)目,。

基金投的50家公司中,有一家發(fā)現(xiàn)向地下注水并在地下巖層之間儲(chǔ)存可長(zhǎng)期儲(chǔ)存能量,。要注水就需要能源,,如果電力充足就能夠做到。然后如果想使用能量就打開井,,放出高壓水為渦輪機(jī)提供動(dòng)力,。

但估計(jì)該創(chuàng)意無法實(shí)現(xiàn)。公司叫Quidnet,,估計(jì)名字是為了致敬哈利·波特之類的。不管怎樣,,資助此人就代表了我們的傾向,。這就是供給側(cè)創(chuàng)新。

需求方同樣必要,,可以用人造肉公司為例,。令人驚訝的是,人造肉市場(chǎng)由消費(fèi)者的選擇驅(qū)動(dòng),。當(dāng)漢堡王開始提供人造肉漢堡時(shí),,需求量非常高,這是好事,。

然而在鋼鐵和水泥行業(yè),,清潔技術(shù)實(shí)在晦澀難懂,,要?jiǎng)?chuàng)造需求就困難得多。航空燃料方面,,清潔燃料的額外成本,,意味著機(jī)票要高出25%。雞尾酒會(huì)上人們可能會(huì)說,,愿意多付25%,。但我懷疑如果真到了緊要關(guān)頭,支付綠色溢價(jià)的消費(fèi)者能否負(fù)擔(dān)總體成本,。

因此,,為鋼鐵水泥產(chǎn)業(yè)打造創(chuàng)新市場(chǎng),比為軟件和醫(yī)療行業(yè)都困難得多,。這可能是突破能源投資設(shè)定了20年有效期和不同的激勵(lì)機(jī)制的原因,。投資者都知道,大多數(shù)公司的成功幾率很小,。

你有沒有想過向公眾投資者開放基金或類似基金,,還有讓人們購買份額以協(xié)助開創(chuàng)需求?

我們還沒有想到這一步,,但我認(rèn)為如果企業(yè)能夠按照每噸價(jià)格估算清楚碳排放量以及成本,,就可以勸說企業(yè)寫支票解決問題。

原則上來說,,這些支票能夠資助基金競(jìng)拍,,可以這么說:“誰能以最低價(jià)格提供清潔鋼鐵?誰能供應(yīng)清潔水泥,?”

所以我比較認(rèn)同,,不管是對(duì)自己的碳足跡感到內(nèi)疚的個(gè)人還是企業(yè),尤其是利潤(rùn)豐厚的企業(yè),,都可以認(rèn)購基金,,就像航天工業(yè)支持太陽能電池板一樣。換句話說就是創(chuàng)造需求,。

這是我想組織的事,。某種程度上人們會(huì)說,“我也為突破能源采購做出了貢獻(xiàn)”,,并為此自豪,。

你可以像沃倫?巴菲特在伯克希爾?哈撒韋那樣,為富裕企業(yè)創(chuàng)建A股,,為其他人創(chuàng)建B股,。

是的,區(qū)分白金和黃金,。

如果說,,能從觀察你長(zhǎng)期得慈善事業(yè)中領(lǐng)悟到什么,,應(yīng)該就是你似乎一直是圍繞著人們所說的先行者做事。如果你可以改造X,,就能夠減少X帶來的不良后果,。

因此,當(dāng)你和梅琳達(dá)創(chuàng)立比爾及梅琳達(dá)蓋茨基金會(huì)時(shí),,合乎邏輯的第一步是投資全球衛(wèi)生,,努力消除瘧疾、腹瀉病,、不受重視的熱帶疾病,、小兒麻痹癥等。當(dāng)然,,減少每年生病和死亡的兒童人數(shù)本身不僅是好事,,理論上也會(huì)帶來一系列好效果。首先,,確保更多健康又有生產(chǎn)力的公民振興發(fā)展中國(guó)家的經(jīng)濟(jì),,就可以減少地方性貧困。

所以如果你能夠解決某件事,,就能對(duì)下游一些事產(chǎn)生積極影響,。基金會(huì)在教育方面的投資也有類似的乘數(shù)效應(yīng),,尤其是年輕女性和女孩的教育方面,。正如梅琳達(dá)所說,5歲以下兒童死亡率的首要指標(biāo)是母親的教育狀況,。如果能解決這個(gè)問題,,就可以幫助一代又一代人脫貧。

其他主要投資上也遵循同樣思路:例如改善衛(wèi)生條件可以減少霍亂,、傷寒,、腹瀉病、痢疾等等,。

現(xiàn)在你大力轉(zhuǎn)向氣候變化領(lǐng)域,,可以說這可能是一系列問題中的終極“先行者”,如果不加以阻止更是如此:要么解決氣候變化問題,,要么迎接世界末日。

如果推理沒問題,,多年來你和梅琳達(dá)關(guān)注的各種事務(wù)中,,氣候變化的地位是不是越來越重要?在各種迫切需求上,,你怎么分配時(shí)間,、注意力和資金,?

在基礎(chǔ)領(lǐng)域,也就是全球健康問題上,,每一美元的影響都是巨大的,。我們拯救每條生命的代價(jià)不到1000美元。之后可能會(huì)出現(xiàn)市場(chǎng)失靈,,因?yàn)榘l(fā)達(dá)國(guó)家并不存在瘧疾,,所以并沒有指導(dǎo)創(chuàng)新者開發(fā)瘧疾藥物和疫苗的市場(chǎng)信號(hào),也沒有消除瘧疾的總體戰(zhàn)略,。瘧疾流行的貧窮國(guó)家卻沒有消除瘧疾的資源,。

我投出第一筆3000萬美元抗擊瘧疾時(shí),成了瘧疾領(lǐng)域最大的資助者,。這可以說是一種悲哀,,這也許是顯著推動(dòng)變革的機(jī)會(huì)。

從事氣候變化的人們都談?wù)撎疾东@,。我是各家公司最大的出資人,,大概投了數(shù)千萬美元,其中包括Climeworks,、Carbon Engineering和Global Thermostat等,。碳捕獲領(lǐng)域有四五家公司。幸運(yùn)的是,,還會(huì)有更多,,因?yàn)樗鼈冇胁煌姆绞健?/p>

每當(dāng)我發(fā)現(xiàn)某些投資,如果成功的話,,每一美元的社會(huì)影響大概能有千倍回報(bào),,我感覺就像風(fēng)險(xiǎn)資本家投了早期谷歌或類似公司一樣。這很吸引我,。

隨著時(shí)間推移,,看到潛在的創(chuàng)新獲得成功,我很開心,。我喜歡和可以同樣看得遠(yuǎn)并愿意保持耐心的人們一起工作,。甚至某些情況下,我們還押注多種途徑,,雖然明知其中一些會(huì)失敗,,例如預(yù)防或治療艾滋病?;ê芏噱X投入到不同方法中,,即使最后只有一種方法奏效,那也是一種奇跡。

關(guān)鍵是創(chuàng)新思維,。有些事,,比如改善美國(guó)的教育,如果采取寬泛的指標(biāo),,如“美國(guó)學(xué)生在數(shù)學(xué),、閱讀和寫作表現(xiàn)如何?”或者“有多少孩子從大學(xué)輟學(xué),?”我們對(duì)全球衛(wèi)生工作的影響還沒有這么大,。

我們?nèi)匀幌嘈盼覀兛梢援a(chǎn)生影響,也在加倍努力,。在疫情期間,,更多孩子真正擁有筆記本電腦并連接互聯(lián)網(wǎng)的想法得到了極大的推動(dòng),真正建立了非常不同的新一代課程,。

即使目前影響幾乎很難察覺的領(lǐng)域,,也還是存在希望。事先不會(huì)知道能發(fā)揮什么作用,。解決問題的大多數(shù)努力都比想象中困難,。

有些事,比如我投錢給Beyond Meat和Impossible Foods時(shí),,從一開始我就說:“改造肉”就像制造零碳鋼和水泥一樣困難?,F(xiàn)在雖然還沒有解決,但已經(jīng)有了出路,。情況跟電動(dòng)汽車差不多,,就是成本降低和質(zhì)量提高,合成人造肉方面的具體表現(xiàn)是,,出現(xiàn)各種生產(chǎn)方式,,綠色溢價(jià)將為零。生產(chǎn)速度真的快到讓我很吃驚,。

書中讓我吃驚是你對(duì)能量?jī)?chǔ)存自然極限的信念,。有些人仍然把希望放在近乎無限大的蓄電池上,或者至少是容量超大的蓄電池,,如此一來可以讓太陽能,、風(fēng)能等途徑獲取的電力更容易儲(chǔ)存。

在我看來,,這也是書中讓人難過的一塊,。儲(chǔ)存能量方面不能應(yīng)用摩爾定律的觀點(diǎn)讓人很難接受。

是啊,,摩爾定律能夠持續(xù)這么久已經(jīng)很令人興奮,。軟件和數(shù)字技術(shù)讓人們認(rèn)為總是有可能出現(xiàn)奇跡,,然而實(shí)際上進(jìn)步更像百年來汽油里程的變化。如果愛迪生復(fù)生看到我們的電池,,他會(huì)說:“哇,這些電池比我發(fā)明的鉛酸電池好四倍,。干得好,。”電池百年創(chuàng)新不過如此,。

人們混淆了電動(dòng)汽車電池和行駛里程的區(qū)別,,里程再擴(kuò)大兩倍就非常理想,而電網(wǎng)儲(chǔ)存的電池目的是夏天收集太陽能,,然后冬天使用,。這個(gè)例子中,一整套電池整體只能夠發(fā)揮一次作用,,即每年可以使用一次電力,。

成本和規(guī)模化非常困難,,我們還有20倍的差距,。我在電池公司虧損的錢比其他企業(yè)都多。現(xiàn)在我在五家電池公司工作,,有幾家直接參與,,也有幾家是通過BEV(突破能源投資公司)。

解決電網(wǎng)問題只有三種方法:一是儲(chǔ)存方面出現(xiàn)奇跡,,二是核裂變,,三是核聚變。只有這些可能性,。

謝謝你,,比爾。

非常感謝,。這次聊天很有趣,。(財(cái)富中文網(wǎng))

譯者:夏林

本文是《財(cái)富》雜志氣候變化突破方案系列報(bào)道的一部分,客座編輯為比爾·蓋茨,。

動(dòng)筆十多年后,,比爾·蓋茨的新書《如何避免氣候?yàn)?zāi)難:我們擁有的解決方案和我們需要的突破》終于面世?!叭绾伪苊狻蹦遣糠肿銎饋聿⒉蝗菀?,但蓋茨計(jì)劃的明確性和緊迫性,可能會(huì)讓數(shù)百萬讀者迅速積極響應(yīng)起來,。

《財(cái)富》雜志希望進(jìn)一步深入挖掘,,探索蓋茨和其他人提出的挑戰(zhàn)。為此,我們邀請(qǐng)這位著名的慈善家擔(dān)任2月16日當(dāng)天《財(cái)富》雜志的“客座編輯”,。

本書出版之前,,《財(cái)富》雜志主編黎克騰,跟微軟聯(lián)合創(chuàng)始人也是投資人蓋茨坐下長(zhǎng)談,,討論如何才能防止氣候變化惡化,,新能源“奇跡”傳遞錯(cuò)誤信息,以及當(dāng)前蓋茨向哪些領(lǐng)域大舉投資,。至于討論中談到了他對(duì)人造肉漢堡(以及其他一些著名投資人的少量“投資目標(biāo)”)的濃厚興趣,,則是意外收獲。

為了簡(jiǎn)潔及表述清晰,,對(duì)話經(jīng)過編輯,。

比爾,你剛剛寫了避免“氣候?yàn)?zāi)難”的書,,然而現(xiàn)在地球上大多數(shù)人都在關(guān)注另一場(chǎng)災(zāi)難——新冠病毒,。你擔(dān)不擔(dān)心讀者可能沒準(zhǔn)備好同時(shí)面對(duì)兩種威脅?

先說說我為什么要寫這本書,。2008年,,在我離開微軟的幾年前,在微軟工作的一些朋友說:“比爾,,你應(yīng)該關(guān)注氣候變化問題,。”

我讀到瓦茨拉夫·斯米爾的書,,對(duì)鋼鐵,、水泥、電力等物質(zhì)經(jīng)濟(jì)產(chǎn)生了濃厚的興趣,。他讓我意識(shí)到,,人們對(duì)輕易獲取各種資源感覺理所當(dāng)然。

比如電力非??煽坑至畠r(jià),,斯米爾在書中談到電力普及方面各種令人驚嘆的工作。當(dāng)然,,這些工作也是導(dǎo)致溫室氣體排放和加劇氣候變化的因素,。所以我開始思考如何改變一切。我在想:“真能實(shí)現(xiàn)嗎,?”

當(dāng)然,,基金會(huì)在貧窮國(guó)家已經(jīng)在做各種工作,經(jīng)濟(jì)欠發(fā)達(dá)國(guó)家的建筑通常是用廢舊金屬建造,。沒有輸電線,。用水方面,,一些地區(qū)的屋頂上裝有小型水箱,因?yàn)楫?dāng)?shù)貨]有給水系統(tǒng),,即便有也極其不可靠,。

后來,朋友介紹我認(rèn)識(shí)了肯·卡爾德拉教授(卡內(nèi)基科學(xué)研究所)和大衛(wèi)·基思教授(目前在哈佛大學(xué)執(zhí)教),。我們一年開六次會(huì),。他們也會(huì)介紹其他專家參加,我們選擇某個(gè)話題,,比如儲(chǔ)存能量、電動(dòng)汽車或煉鋼,,提前閱讀大量材料,,然后討論半天。我對(duì)相關(guān)話題非常感興趣,。

我的理解框架其實(shí)不少,,2010年我在TED發(fā)表了演講(題目叫“從零開始創(chuàng)新”),一共講了三場(chǎng),。其中一場(chǎng)關(guān)于政府預(yù)算問題在哪,,我保證總有一天這會(huì)被當(dāng)成預(yù)言;2015年的演講關(guān)于疫病,,可能是到現(xiàn)在瀏覽量最高的一場(chǎng)(編者按:該場(chǎng)有先見之明的TED演講標(biāo)題是“下一次大爆發(fā),?我們還沒有準(zhǔn)備好?!蹦壳盀g覽量已經(jīng)達(dá)到3900萬次,。);關(guān)于氣候的那場(chǎng)并不長(zhǎng),。我想想,,大概15分鐘?——可以找來看看,。

那場(chǎng)演講的目的是:“困難太大,,需要?jiǎng)?chuàng)新——很多創(chuàng)新?!北M管我現(xiàn)在比十年前知道得更多,,但那仍然是我的基本認(rèn)識(shí)框架,也是新書的框架,。

但就像現(xiàn)在一樣,,十年前你在TED上發(fā)表關(guān)于氣候變化的演講時(shí),全世界也被另一場(chǎng)全球危機(jī)分散了注意力,。

不幸的是,,2010年左右那段時(shí)間里,,也就是金融危機(jī)之后,(應(yīng)對(duì))氣候變化的能源消耗大幅下降,。然后隨著經(jīng)濟(jì)開始復(fù)蘇,,興趣稍微上升。

對(duì)我來說,,之后一個(gè)重大里程碑是2015年巴黎氣候談判之前一年,,當(dāng)時(shí)我對(duì)大家說:“為什么人們開這些會(huì)議,卻不討論研發(fā)預(yù)算和刺激創(chuàng)新的想法,?”

大概結(jié)構(gòu)是:“我們以國(guó)家身份來談?wù)劷谶M(jìn)展,。”最近在風(fēng)能,、太陽能發(fā)電,,以及電動(dòng)汽車應(yīng)用方面有些進(jìn)展。并不是說這些事情很容易,,但這都是最容易做到減排的手段,。

所以當(dāng)你說:“五年后或者十年后能夠做什么?”人們并不會(huì)答:“我正用全新的方式煉鐵,?!币?yàn)楦鲊?guó)煉鐵方式差別不大。鋼鐵在全球都是具有競(jìng)爭(zhēng)力的行業(yè),。因此,,溫室氣體排放70%以上的來源從未出現(xiàn)在“讓我們討論下短期減排”的討論中。奇怪的是,,真正難推動(dòng)的領(lǐng)域幾乎沒人討論過,,占排放70%的鋼鐵、水泥或航空就是很好的例子,。

但到了2015年,,在COP21(跟當(dāng)年巴黎聯(lián)合國(guó)氣候變化大會(huì)同時(shí)舉辦的可持續(xù)創(chuàng)新論壇)上,這問題被提了出來,。

法國(guó)組織者想做一些不同的事情,,他們希望(印度總理納倫德拉)莫迪能來。莫迪并不想?yún)?huì),,然后被追問“短期減排多少,?”因?yàn)橛《鹊碾娏π枨笫乾F(xiàn)在的五倍,,才可以讓大部分人口維持基本的生活方式,。所以他不會(huì)出席,。

但是,,COP21的附帶結(jié)果也就是所謂的使命創(chuàng)新,,不僅關(guān)注增加能源研發(fā)預(yù)算,,還要確保有私營(yíng)部門投資者愿意承擔(dān)風(fēng)險(xiǎn),,將有希望的創(chuàng)意轉(zhuǎn)化為公司,前提是研發(fā)實(shí)驗(yàn)室將創(chuàng)意變?yōu)楝F(xiàn)實(shí),。

當(dāng)時(shí),,Kleiner Perkins的約翰?多爾或維諾德?科斯拉的風(fēng)投基金做了大量綠色投資,,業(yè)績(jī)并不好。Kleiner Perkins賭的是菲斯克(汽車)而不是特斯拉,。很多太陽能電池板方面的(投資)并不順利,。所以我承諾籌錢向該領(lǐng)域投資。

后來就成立了突破能源風(fēng)投基金,,隸屬于我旗下主要關(guān)注氣候變化的機(jī)構(gòu),。公司覆蓋幾個(gè)不同的領(lǐng)域,,包括專注政策解決方案的部門。不過當(dāng)前主要是從事風(fēng)投,。

我們籌集了剛好10億多美元,,現(xiàn)在投資了50家公司,,進(jìn)展很順利,。我們也找了其他人投資,。

本書出版的時(shí)候(2月16日),,我們稱之為BEV2的風(fēng)投基金已經(jīng)融到數(shù)十億美元,,將繼續(xù)投50家公司,,其中大部分都會(huì)失敗。即便是成功也比典型的軟件公司更難,,因?yàn)樾枰度氪罅抠Y金,,還需要產(chǎn)業(yè)合作關(guān)系。所以這是完全不同的投資方式,,我的目標(biāo)是幫助擴(kuò)大創(chuàng)新規(guī)模,。

但是,就在你擴(kuò)大投資規(guī)模還召集其他投資者和決策者關(guān)注能源領(lǐng)域的激進(jìn)創(chuàng)新時(shí),,趕上了新冠疫情,。你似乎把注意力和慈善事業(yè)放在尋找新冠治療方法和疫苗上,去年9月你接受《財(cái)富》雜志采訪時(shí)談到過,。

這應(yīng)該夸一夸這一代的人們,,即便當(dāng)前身處疫情中,大家也還是真正關(guān)心氣候危機(jī)的,。

這次不像金融危機(jī)(2007年-2008年)期間,,當(dāng)時(shí)人們說,“現(xiàn)在情況很艱難,,沒有工夫管氣候變化,。”即便到2010年,,如果對(duì)公眾民意調(diào)查,,也會(huì)發(fā)現(xiàn)人們對(duì)氣候的興趣已經(jīng)下降。

而在接下來十年里,,關(guān)注又逐漸增加,,遭遇疫情時(shí)我還在想:“會(huì)出現(xiàn)什么情況?”實(shí)際上,,疫情期間人們對(duì)氣候變化的關(guān)注有所上升,,這有點(diǎn)奇怪。

看看拜登總統(tǒng)挑選的專家,,也是差不多情況,,這屆政府里,有很多氣候問題專家,??偨y(tǒng)正關(guān)注著幾個(gè)互相疊加的危機(jī),疫情和氣候變化重要性相當(dāng),這點(diǎn)相當(dāng)讓人贊嘆,。

而且總統(tǒng)初選和大選期間,,候選人遇到的氣候問題數(shù)量比以往都要多。再看看歐洲的復(fù)蘇計(jì)劃,,資本投資也極其傾向氣候變化領(lǐng)域,。超過三分之一的資金都與此有關(guān)。

所以我感覺很幸運(yùn),,在某種程度上年輕人提升了話題的重要性,。我年輕的時(shí)候都沒做到。當(dāng)時(shí)我都沒上街游行,。

我的觀點(diǎn)是,,“既然你們?nèi)绱岁P(guān)心,而且能夠理想主義地說:‘讓我們盡一切努力在2050年之前實(shí)現(xiàn)零排放’——就應(yīng)該制定相應(yīng)的計(jì)劃,,根據(jù)計(jì)劃逆推,,然后說:‘鋼鐵、水泥和航空要怎么做,?’”

不希望人們想:“哦,,我們只想確保多裝幾個(gè)太陽能電池板?!比缓?0年過去,,排放并沒有什么變化。

所以除非計(jì)劃得當(dāng),,否則最后只會(huì)引發(fā)很多憤世嫉俗和失望,。

所以你決定把計(jì)劃寫成書。

是的,,新書主要說的是計(jì)劃,。書中沒具體解釋為什么氣候變化有害,但還是用一章的篇幅大概講了講,,還有一章關(guān)于適應(yīng)的。但書中大部分內(nèi)容主要還是類似于:“溫室氣體排放達(dá)510億噸,,以下列舉出排放的領(lǐng)域,。”看看各領(lǐng)域的情況,,然后說:“如果想實(shí)現(xiàn)零排放,,達(dá)到同樣產(chǎn)量成本的情況下,要貴多少,?”

這就是我說的綠色溢價(jià)指標(biāo),。我們能夠討論的是:“當(dāng)今水泥的綠色溢價(jià)是多少?哪家公司的技術(shù)能夠?qū)崿F(xiàn)減半?有沒有可能降到零,?”

將綠色溢價(jià)降到零是很神奇的,,未來十年電動(dòng)汽車將能實(shí)現(xiàn)這個(gè)目標(biāo)。也就是說,,不需要政府資助創(chuàng)新,,也不需要個(gè)人資助。只要量達(dá)到一定程度,,產(chǎn)品變得便宜,,充電站也變得普及,政客就可以參與,。

到時(shí)政客就能夠說,,2035年、2040年之前禁止燃油車,,公眾不會(huì)震驚地問:“什么,?!”

如果綠色溢價(jià)降到接近零,,相關(guān)政策的實(shí)行就成為可能,,不過在大量碳排放的地區(qū)也要采取同樣措施。有些領(lǐng)域,,比如鋼鐵或水泥生產(chǎn)實(shí)施起來都很困難,。不管怎樣,這都是最基本的,。

我非常喜歡這本書的一點(diǎn)是,,讀者可以體驗(yàn)學(xué)習(xí)氣候科學(xué)的過程。舉例來說,,你對(duì)汽油比蘇打水便宜感到驚奇,,或者解釋為什么某些氣體吸收或反射太陽輻射取決于原子組成時(shí),感覺好像你正在高興地跟讀者分享發(fā)現(xiàn),。在寫書的過程中,,你有沒有意識(shí)到要分享個(gè)人發(fā)現(xiàn)之旅?

對(duì)我來說,,所有東西都很有趣,。

當(dāng)你在其他某些地方讀到相關(guān)內(nèi)容時(shí),對(duì)內(nèi)容的解釋經(jīng)常并不清晰,,比方說,,你會(huì)讀到文章說:“減排力度相當(dāng)于10000戶或40000輛汽車?!?/p>

你得想:“我得費(fèi)勁理解數(shù)字,,總數(shù)是多少,,然后算這些數(shù)字占多少?”

我想把數(shù)字簡(jiǎn)化,,如果有人談到10000戶或40000輛汽車碳減排時(shí),,我就能夠回答這個(gè)問題:“占總碳排放量的百分比是多少?”

大多數(shù)人讀到相關(guān)文章時(shí)會(huì)說:“這些都只是胡言亂語,?!碑?dāng)一開始努力理解時(shí),能量單位都非常大,,容易讓人感覺混亂,。對(duì)我來說,能夠利用某些熟悉的事物去理解比較有吸引力,。

必須承認(rèn),,這本書非常感謝肯·卡爾德拉和大衛(wèi)·基思,他們向我傳授了很多知識(shí),,還介紹了很多人,。

還有像(微軟前首席技術(shù)官)內(nèi)森·米爾沃德和(多產(chǎn)發(fā)明家)洛厄爾·伍德等人,每當(dāng)我對(duì)物理或化學(xué)方面有疑惑時(shí),,就給他們寫郵件,。當(dāng)然還有瓦茨拉夫·斯米爾,他寫了很多書,,對(duì)諸如1800年工業(yè)經(jīng)濟(jì)的概況和之后的重大突破的著迷,,為我提供了靈感。

我很喜歡研究這些,。其實(shí)很簡(jiǎn)單,。跟大多數(shù)領(lǐng)域一樣,就這么幾個(gè)概念,,但必須真正了解它們,。

比如能量速率、能源數(shù)量,,以及儲(chǔ)存時(shí)間,。

對(duì)能源來說,這些相當(dāng)于“能不能想用的時(shí)候就用,?”斯米爾做了直觀展示,,“一座城市耗能量多少,或者一個(gè)家庭耗能量多少,?”這樣腦中就能理解各種數(shù)字和常識(shí)。

為了理解,,我?guī)鹤尤ッ旱V工廠,,還去了水泥廠和造紙廠實(shí)地參觀。因?yàn)槲覀冎欢浖诨瘜W(xué)實(shí)驗(yàn)方面實(shí)在不擅長(zhǎng),。

以前我想的是:“只算化學(xué)方程式就好,,別用試管實(shí)際操作。我可能造成爆炸,?!?/p>

成長(zhǎng)過程中,我從沒有造過小火車或飛機(jī)之類的物品,。所以我一直覺得:“上帝,,實(shí)體的東西才是真的?!?/p>

我是說,,得有人真去建造機(jī)器和工廠。

不管怎樣,,學(xué)習(xí)很有趣,。如果告訴別人我花了多少時(shí)間或者讀了多少書,就得小心點(diǎn),,因?yàn)槁犉饋硐袷谴蹬J裁吹?。但我最大的?yōu)點(diǎn)就是喜歡當(dāng)學(xué)生。

我很喜歡的說法是,,只要了解得足夠多,,實(shí)際上什么事情都很簡(jiǎn)單。我有足夠的信心,,還有很聰明的朋友,,他們會(huì)幫我達(dá)到目標(biāo),我可以說:“我要學(xué)習(xí),,最終達(dá)到一切都能夠解釋通的程度,。”

在書中的某些部分,,你似乎在凝視未來,。去年秋天我讀到第一版書稿中,你提到“美國(guó)退出2015年巴黎協(xié)議”,,還說“之后美國(guó)總統(tǒng)拜登會(huì)將其逆轉(zhuǎn)”,。你早在美國(guó)總統(tǒng)大選前就能夠預(yù)測(cè)到,真令人驚訝,。

書中的大部分內(nèi)容實(shí)際上是在10個(gè)月前就完成了的,。我當(dāng)時(shí)考慮了很久,要不要出版,。

剛開始問題是,,如果特朗普連任,,顯然會(huì)影響美國(guó)按照書中呼吁行事的能力。這本書主要關(guān)于創(chuàng)新,,美國(guó)控制著當(dāng)今世界50%以上的創(chuàng)新能力,,創(chuàng)新會(huì)發(fā)生在大學(xué)里、國(guó)家實(shí)驗(yàn)室里,,還有風(fēng)險(xiǎn)投資當(dāng)中,。如果不讓美國(guó)推動(dòng)創(chuàng)新,那么全世界創(chuàng)新都會(huì)停滯,。因?yàn)樵诿绹?guó),,創(chuàng)新不僅僅為了本國(guó)公民,也為了其他人,。

如果我們可以廉價(jià)制造清潔(無碳)水泥,,30年后當(dāng)發(fā)展中國(guó)家為人民建造住房時(shí)也會(huì)選擇清潔水泥。

所以當(dāng)我寫作時(shí),,最后幾章變得非常復(fù)雜,,我不得不琢磨措辭,“如果民主黨候選人當(dāng)選……”等等,。

還有疫情來襲,,我想,“哦,,人們注意力可能有點(diǎn)分散,。”

所以在大選后,,我決定對(duì)書做點(diǎn)修訂,,也許增加一些技術(shù)進(jìn)展。大選后我對(duì)書完整檢查了一遍,,又加了些內(nèi)容,。

從第一章到第九章,幾乎沒有重大修訂,。但到了第10章至第12章,,談及政府政策等相關(guān)問題時(shí),我做了相當(dāng)多修改,。即使民主黨控制了白宮和國(guó)會(huì),、參議院幾乎平分秋色,而且美國(guó)已經(jīng)陷入赤字,,我們也必須拿出不需要大量資源的計(jì)劃,。

這是可行的,我相當(dāng)樂觀,。

其中涉及的政治太復(fù)雜,。在第11章路線圖中,,你提出了激勵(lì)和抑制或懲罰政策措施,也就是胡蘿卜和大棒,。但過去我們看到,棍子更難到位,。

以《平價(jià)醫(yī)療法案》為例,,行政部門和國(guó)會(huì)兩院中民主黨占多數(shù),僅僅是個(gè)人授權(quán)和相關(guān)處罰的概念就已經(jīng)導(dǎo)致立法內(nèi)戰(zhàn),,而且到如今仍在持續(xù),。

我讀到書中關(guān)于碳價(jià)格設(shè)定部分,實(shí)際上是“碳稅”,,稅率高到能夠抵消綠色溢價(jià),,我想知道你對(duì)近期實(shí)現(xiàn)的把握有多大?正如你寫到:“為碳排放定價(jià),,是消除綠色溢價(jià)能做的關(guān)鍵事項(xiàng)之一,。”

如果沒有創(chuàng)新,,即便碳捕獲可以降到比方每噸100美元,,仍然要面臨巨大挑戰(zhàn),因?yàn)槊磕晏寂欧帕坑?10億噸,。在世界上某個(gè)地方必須找到每年5萬億美元的支出,,占世界經(jīng)濟(jì)5%以上。這是不可能的,,沒機(jī)會(huì),。

當(dāng)然,從政治上征收任何形式的碳稅都非常困難,。法國(guó)試圖提高柴油價(jià)格時(shí),,人們大喊:“嘿,不能這么做,!”類似努力不可避免地被減弱,,因?yàn)閷?shí)施起來的收獲與人們的感受并不成比例。

可以嘗試進(jìn)行彌補(bǔ),,但在法國(guó)的例子中,,住在城市之外不得不開車趕路的人,覺得住在城市的精英忽視了自己,,這也是各個(gè)富裕國(guó)家普遍存在的政治現(xiàn)象,。最終法國(guó)還是廢除了柴油稅。

現(xiàn)在公眾不太愿意掏錢避免負(fù)面影響,,畢竟這些負(fù)面影響大多在遙遠(yuǎn)的未來,。我是說,,確實(shí)有一些有關(guān)天氣的負(fù)面現(xiàn)象已經(jīng)顯露,比如森林火災(zāi),,還有非常炎熱的日子,。

很高興人們已經(jīng)注意到,如果目前不采取行動(dòng),,如今的負(fù)面影響將無法與2080年和2100年的境遇相比,,對(duì)生活在赤道附近的人來說更是如此。到2100年,,夏天在印度戶外活動(dòng)將難以忍受,。戶外工作根本不可能,畢竟身體的排汗量是有限的,。

書中接近結(jié)尾的地方,,你總結(jié)實(shí)現(xiàn)零排放的計(jì)劃時(shí)談到“加速創(chuàng)新需求”。這一概念似乎對(duì)成功非常關(guān)鍵,,而且似乎跟你在慈善事業(yè)中做的很多工作也有所不同,。你跟梅琳達(dá)創(chuàng)立的基金會(huì)經(jīng)常資助創(chuàng)新投資的公司。但在一些根本不存在市場(chǎng)的地方開創(chuàng)建立需求側(cè),,是另一種挑戰(zhàn),。

例如在制藥行業(yè),制藥巨頭通過大量生物技術(shù)初創(chuàng)公司為創(chuàng)新提供市場(chǎng),,跟有希望治療某種適應(yīng)癥的實(shí)驗(yàn)候選藥物競(jìng)爭(zhēng),。氣候方面是否也有類似模式,即能源巨頭為能源初創(chuàng)企業(yè)在零排放方面的進(jìn)展提供現(xiàn)成市場(chǎng),?還是像國(guó)防工業(yè)創(chuàng)新一樣,,“市場(chǎng)”必須由政府提供?

能源方面難得多,。相比之下,,軟件反而最簡(jiǎn)單。醫(yī)學(xué)的難度介于中間,。與氣候有關(guān)的事情最困難,。

軟件方面,總有一些客戶不喜歡現(xiàn)有的軟件,,認(rèn)為應(yīng)該更簡(jiǎn)單,、更便宜,或者在某些方面功能更多,。只要能從壟斷巨頭那里搶來一小塊市場(chǎng),,就可以服務(wù)某些客戶,因?yàn)槟隳軌蚋玫貪M足需求。軟件創(chuàng)新者面前有現(xiàn)成的市場(chǎng),。

醫(yī)藥也一樣,。看看各種各樣的疾病,,也許新產(chǎn)品是口服而不是注射,,或者能夠減少一些副作用?;蛘?,希望每隔一段時(shí)間找到全新的方法治療不治之癥。但這一行業(yè)同時(shí)也要面臨各種監(jiān)管,、檢查和副作用等問題。

氣候變化方面最困難的是,,制造清潔鋼鐵除了能夠保護(hù)地球之外,,并沒有額外益處。如果僅僅是跟傳統(tǒng)上公認(rèn)的工藝略有不同,,買家很可能發(fā)出疑問:“耐用嗎,,會(huì)變脆嗎,會(huì)生銹嗎,?”

人們對(duì)任何變化都抱著懷疑態(tài)度,。因?yàn)殇撹F非常可靠,,水泥也一樣,。有個(gè)公式可以精確計(jì)算強(qiáng)度,測(cè)試本身不是為了測(cè)試特性,,只是測(cè)試是否遵循了公式,。因此,市場(chǎng)中并沒有專門一塊愿意為清潔鋼鐵或水泥支付更高價(jià)格的,。

現(xiàn)在太陽能電池板的情況是,,衛(wèi)星需要能源,太陽能電池板是唯一的方法,。哪怕不經(jīng)濟(jì),,德國(guó)和日本也買了。量不大,,但足夠啟動(dòng)學(xué)習(xí)曲線,。然后包括美國(guó)在內(nèi)其他國(guó)家實(shí)施稅收抵免,學(xué)習(xí)曲線逐漸擴(kuò)大,。

我們已經(jīng)看到學(xué)習(xí)曲線模式在風(fēng)能和鋰離子電池上的應(yīng)用,,這是算是奇跡。

可悲的是,,大多數(shù)人認(rèn)為,,“電池做得夠汽車用,,就可以做得能夠讓整個(gè)電網(wǎng)都用,我們要在電網(wǎng)創(chuàng)造另一個(gè)奇跡,?!钡麄儧]有意識(shí)到,很多希望創(chuàng)造奇跡的嘗試,,比如燃料電池或氫動(dòng)力汽車都還沒有成功,。

舉個(gè)例子,在裂變動(dòng)力核反應(yīng)堆方面,,創(chuàng)新還有其他難點(diǎn),。成本和安全問題引發(fā)的擔(dān)憂非常大,除非用全新設(shè)計(jì)重建反應(yīng)堆,,在經(jīng)濟(jì)性和安全性上徹底革新,,否則前路只會(huì)是死胡同。這就是我在(核能公司)TerraPower(蓋茨擔(dān)任董事會(huì)主席)努力做的事情,。

如果把過往的成功投射到這些領(lǐng)域,,最后可能認(rèn)為事情比實(shí)際情況簡(jiǎn)單得多。你提的問題非常好,,因?yàn)闀忻枋稣w戰(zhàn)略的一部分,,就是為清潔鋼材找買家。

假設(shè)現(xiàn)在綠色溢價(jià)是每噸100美元,。有人創(chuàng)辦一家每噸溢價(jià)僅50美元的清潔鋼鐵公司,,你會(huì)對(duì)那個(gè)人說:“干得好!”但事實(shí)上市場(chǎng)規(guī)模為零,,因?yàn)槊繃嵍喑?0美元,,只意味著成本更高。

現(xiàn)在我們要做的是努力讓資金更充裕的公司,,比如科技巨頭同意每當(dāng)建造新大樓,,就要使用20%的清潔鋼材?;貓?bào)是可以對(duì)外宣稱:“大樓用了20%的清潔鋼材,。”

所以我們得創(chuàng)造需求側(cè),。我熱愛創(chuàng)新的供給端,,要去找教授,找有瘋狂創(chuàng)意的人,。所以突破能源投資公司有很多類似的項(xiàng)目,。

基金投的50家公司中,有一家發(fā)現(xiàn)向地下注水并在地下巖層之間儲(chǔ)存可長(zhǎng)期儲(chǔ)存能量。要注水就需要能源,,如果電力充足就能夠做到,。然后如果想使用能量就打開井,放出高壓水為渦輪機(jī)提供動(dòng)力,。

但估計(jì)該創(chuàng)意無法實(shí)現(xiàn),。公司叫Quidnet,估計(jì)名字是為了致敬哈利·波特之類的,。不管怎樣,,資助此人就代表了我們的傾向。這就是供給側(cè)創(chuàng)新,。

需求方同樣必要,,可以用人造肉公司為例。令人驚訝的是,,人造肉市場(chǎng)由消費(fèi)者的選擇驅(qū)動(dòng),。當(dāng)漢堡王開始提供人造肉漢堡時(shí),需求量非常高,,這是好事。

然而在鋼鐵和水泥行業(yè),,清潔技術(shù)實(shí)在晦澀難懂,,要?jiǎng)?chuàng)造需求就困難得多。航空燃料方面,,清潔燃料的額外成本,,意味著機(jī)票要高出25%。雞尾酒會(huì)上人們可能會(huì)說,,愿意多付25%,。但我懷疑如果真到了緊要關(guān)頭,支付綠色溢價(jià)的消費(fèi)者能否負(fù)擔(dān)總體成本,。

因此,,為鋼鐵水泥產(chǎn)業(yè)打造創(chuàng)新市場(chǎng),比為軟件和醫(yī)療行業(yè)都困難得多,。這可能是突破能源投資設(shè)定了20年有效期和不同的激勵(lì)機(jī)制的原因,。投資者都知道,大多數(shù)公司的成功幾率很小,。

你有沒有想過向公眾投資者開放基金或類似基金,,還有讓人們購買份額以協(xié)助開創(chuàng)需求?

我們還沒有想到這一步,,但我認(rèn)為如果企業(yè)能夠按照每噸價(jià)格估算清楚碳排放量以及成本,,就可以勸說企業(yè)寫支票解決問題。

原則上來說,這些支票能夠資助基金競(jìng)拍,,可以這么說:“誰能以最低價(jià)格提供清潔鋼鐵,?誰能供應(yīng)清潔水泥?”

所以我比較認(rèn)同,,不管是對(duì)自己的碳足跡感到內(nèi)疚的個(gè)人還是企業(yè),,尤其是利潤(rùn)豐厚的企業(yè),都可以認(rèn)購基金,,就像航天工業(yè)支持太陽能電池板一樣,。換句話說就是創(chuàng)造需求。

這是我想組織的事,。某種程度上人們會(huì)說,,“我也為突破能源采購做出了貢獻(xiàn)”,并為此自豪,。

你可以像沃倫?巴菲特在伯克希爾?哈撒韋那樣,,為富裕企業(yè)創(chuàng)建A股,為其他人創(chuàng)建B股,。

是的,,區(qū)分白金和黃金。

如果說,,能從觀察你長(zhǎng)期得慈善事業(yè)中領(lǐng)悟到什么,,應(yīng)該就是你似乎一直是圍繞著人們所說的先行者做事。如果你可以改造X,,就能夠減少X帶來的不良后果,。

因此,當(dāng)你和梅琳達(dá)創(chuàng)立比爾及梅琳達(dá)蓋茨基金會(huì)時(shí),,合乎邏輯的第一步是投資全球衛(wèi)生,,努力消除瘧疾、腹瀉病,、不受重視的熱帶疾病,、小兒麻痹癥等。當(dāng)然,,減少每年生病和死亡的兒童人數(shù)本身不僅是好事,,理論上也會(huì)帶來一系列好效果。首先,,確保更多健康又有生產(chǎn)力的公民振興發(fā)展中國(guó)家的經(jīng)濟(jì),,就可以減少地方性貧困。

所以如果你能夠解決某件事,,就能對(duì)下游一些事產(chǎn)生積極影響,?;饡?huì)在教育方面的投資也有類似的乘數(shù)效應(yīng),尤其是年輕女性和女孩的教育方面,。正如梅琳達(dá)所說,,5歲以下兒童死亡率的首要指標(biāo)是母親的教育狀況。如果能解決這個(gè)問題,,就可以幫助一代又一代人脫貧,。

其他主要投資上也遵循同樣思路:例如改善衛(wèi)生條件可以減少霍亂、傷寒,、腹瀉病,、痢疾等等。

現(xiàn)在你大力轉(zhuǎn)向氣候變化領(lǐng)域,,可以說這可能是一系列問題中的終極“先行者”,,如果不加以阻止更是如此:要么解決氣候變化問題,,要么迎接世界末日。

如果推理沒問題,,多年來你和梅琳達(dá)關(guān)注的各種事務(wù)中,氣候變化的地位是不是越來越重要,?在各種迫切需求上,,你怎么分配時(shí)間,、注意力和資金,?

在基礎(chǔ)領(lǐng)域,,也就是全球健康問題上,每一美元的影響都是巨大的,。我們拯救每條生命的代價(jià)不到1000美元。之后可能會(huì)出現(xiàn)市場(chǎng)失靈,,因?yàn)榘l(fā)達(dá)國(guó)家并不存在瘧疾,,所以并沒有指導(dǎo)創(chuàng)新者開發(fā)瘧疾藥物和疫苗的市場(chǎng)信號(hào),也沒有消除瘧疾的總體戰(zhàn)略,。瘧疾流行的貧窮國(guó)家卻沒有消除瘧疾的資源,。

我投出第一筆3000萬美元抗擊瘧疾時(shí),成了瘧疾領(lǐng)域最大的資助者,。這可以說是一種悲哀,,這也許是顯著推動(dòng)變革的機(jī)會(huì),。

從事氣候變化的人們都談?wù)撎疾东@。我是各家公司最大的出資人,,大概投了數(shù)千萬美元,,其中包括Climeworks、Carbon Engineering和Global Thermostat等,。碳捕獲領(lǐng)域有四五家公司,。幸運(yùn)的是,還會(huì)有更多,,因?yàn)樗鼈冇胁煌姆绞健?/p>

每當(dāng)我發(fā)現(xiàn)某些投資,,如果成功的話,每一美元的社會(huì)影響大概能有千倍回報(bào),,我感覺就像風(fēng)險(xiǎn)資本家投了早期谷歌或類似公司一樣,。這很吸引我。

隨著時(shí)間推移,,看到潛在的創(chuàng)新獲得成功,我很開心,。我喜歡和可以同樣看得遠(yuǎn)并愿意保持耐心的人們一起工作,。甚至某些情況下,,我們還押注多種途徑,,雖然明知其中一些會(huì)失敗,例如預(yù)防或治療艾滋病,。花很多錢投入到不同方法中,,即使最后只有一種方法奏效,,那也是一種奇跡,。

關(guān)鍵是創(chuàng)新思維,。有些事,比如改善美國(guó)的教育,,如果采取寬泛的指標(biāo),,如“美國(guó)學(xué)生在數(shù)學(xué),、閱讀和寫作表現(xiàn)如何,?”或者“有多少孩子從大學(xué)輟學(xué),?”我們對(duì)全球衛(wèi)生工作的影響還沒有這么大,。

我們?nèi)匀幌嘈盼覀兛梢援a(chǎn)生影響,也在加倍努力,。在疫情期間,,更多孩子真正擁有筆記本電腦并連接互聯(lián)網(wǎng)的想法得到了極大的推動(dòng),真正建立了非常不同的新一代課程,。

即使目前影響幾乎很難察覺的領(lǐng)域,,也還是存在希望。事先不會(huì)知道能發(fā)揮什么作用,。解決問題的大多數(shù)努力都比想象中困難,。

有些事,比如我投錢給Beyond Meat和Impossible Foods時(shí),,從一開始我就說:“改造肉”就像制造零碳鋼和水泥一樣困難?,F(xiàn)在雖然還沒有解決,但已經(jīng)有了出路,。情況跟電動(dòng)汽車差不多,,就是成本降低和質(zhì)量提高,合成人造肉方面的具體表現(xiàn)是,,出現(xiàn)各種生產(chǎn)方式,,綠色溢價(jià)將為零。生產(chǎn)速度真的快到讓我很吃驚,。

書中讓我吃驚是你對(duì)能量?jī)?chǔ)存自然極限的信念,。有些人仍然把希望放在近乎無限大的蓄電池上,或者至少是容量超大的蓄電池,,如此一來可以讓太陽能,、風(fēng)能等途徑獲取的電力更容易儲(chǔ)存。

在我看來,,這也是書中讓人難過的一塊,。儲(chǔ)存能量方面不能應(yīng)用摩爾定律的觀點(diǎn)讓人很難接受,。

是啊,,摩爾定律能夠持續(xù)這么久已經(jīng)很令人興奮。軟件和數(shù)字技術(shù)讓人們認(rèn)為總是有可能出現(xiàn)奇跡,,然而實(shí)際上進(jìn)步更像百年來汽油里程的變化,。如果愛迪生復(fù)生看到我們的電池,他會(huì)說:“哇,,這些電池比我發(fā)明的鉛酸電池好四倍,。干得好,。”電池百年創(chuàng)新不過如此,。

人們混淆了電動(dòng)汽車電池和行駛里程的區(qū)別,,里程再擴(kuò)大兩倍就非常理想,而電網(wǎng)儲(chǔ)存的電池目的是夏天收集太陽能,,然后冬天使用,。這個(gè)例子中,一整套電池整體只能夠發(fā)揮一次作用,,即每年可以使用一次電力,。

成本和規(guī)模化非常困難,,我們還有20倍的差距,。我在電池公司虧損的錢比其他企業(yè)都多。現(xiàn)在我在五家電池公司工作,,有幾家直接參與,,也有幾家是通過BEV(突破能源投資公司)。

解決電網(wǎng)問題只有三種方法:一是儲(chǔ)存方面出現(xiàn)奇跡,,二是核裂變,,三是核聚變。只有這些可能性,。

謝謝你,,比爾。

非常感謝,。這次聊天很有趣,。(財(cái)富中文網(wǎng))

譯者:夏林

This article is part of Fortune’s Blueprint for a climate breakthrough package, guest edited by Bill Gates.

More than a decade in the works, Bill Gates’ new book, How to Avoid a Climate Disaster, hits shelves today. The “how to” part is anything but easy. But the clarity of Gates’s plan—and the reason for absolute urgency—may well turn millions of readers into overnight activists. (It should.) At Fortune, we wanted to dig deeper, exploring the challenges that Gates raises and a bunch of others as well. To that end, we’ve asked the famous philanthropist to serve as “guest editor” of Fortune for the day.

In advance of the book’s publication, Fortune editor-in-chief Clifton Leaf also sat down with the Microsoft cofounder and high-stakes venture investor for a sprawling conversation about what needs to be done now to stop climate change in its tracks, the energy “miracles” that are sending the wrong message, and where he’s placing his multimillion-dollar bets right now. That our discussion took us to his fascination with the Impossible Burger (and a smattering of “dish” on some other famous investors) is just gravy.

The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Bill, you’ve just written a playbook for avoiding a “climate disaster” when much of the planet is still focused on another disaster—the coronavirus. Did you have any concern that readers might not be ready to engage with two existential threats at the same time?

So just a little bit, first, about why I wrote the book. It was a few years before I left Microsoft in 2008 that some friends who worked there said, “You know, Bill, you should get involved in the issue of climate change.”

I had already developed a fascination about the physical economy—things like steel, cement, electricity—by reading Vaclav Smil. He got me thinking about the fact that we take the ease of these things for granted. Electricity, for example, is so reliable and so cheap, and Smil talks about all the amazing work that went into that. But these are things that contribute to greenhouse gases and driving climate change, of course. So I began thinking about the idea that this was all going to have to change. And I thought, “Is that really gonna happen?”

Of course, the foundation was doing all this work in poor countries, where buildings are often built out of scrap metal. There are no transmission wires. For water, in some places, they have little tanks up on their roofs because the distribution system doesn’t exist or if it does, it’s super unreliable.

So anyway, my friends introduced me to a couple professors—Ken Caldeira [at the Carnegie Institution for Science] and David Keith [who’s now at Harvard]. And I think we started meeting six times a year. They would bring other experts in, and we would take a topic like storing energy or electric cars or making steel, and we’d have a half-day discussion with a lot of reading in advance. I was fascinated with the topic.

And I had enough of a framework that I gave a TED Talk in 2010 [called “Innovating to Zero”]; I have three given three of those talks. I have one about how government budgets are a problem—and I promise you, someday that will be viewed as an advanced warning. I have the 2015 one on the pandemic, which is now probably the most viewed thing I’ve ever done. [Editor’s note: That prescient TED talk, “The next outbreak? We’re not ready,” has now been viewed 39 million times.] But the one on climate—it’s not very long. I think, what is it, 15 minutes?—you might look at that.

The point of that talk was to say, “Look, this is superhard and requires innovation—a lot of innovation.” And even though I know a lot more today than I did a decade ago, that’s still my basic framework. I have to admit, that’s my basic framework for anything. That’s the framework for the book.

But just as it is now, the world was also a little distracted by another global crisis a decade ago when you gave your TED Talk on climate change.

Unfortunately, in that time period—circa 2010, after the financial crisis—the energy [for addressing] climate change goes way down. And then, as the economy starts to recover, interest goes up a little bit. So the next big milestone for me was the year in advance of the Paris climate talks in 2015 when I was saying to everybody, “Hey, how come they have these meetings and the idea of an R&D budget and spurring innovation is not in the meeting?”

The framework is just, “Hey, let’s come in as countries and talk about our near-term progress.” And there has been near-term progress using wind and solar for electricity generation and using battery electric-powered cars. And I’m not saying those things are easy, but those are the easiest sources of emissions to lower. And so whenever you’re just saying, “Okay, what can you do five years from now, or 10 years from now?” nobody comes to the meeting and says, “Okay, I’m making my steel a whole new way.” Because making steel is not something one country does differently than other countries. Steel is a globally competitive industry. And so the various sources that cause over 70% of our greenhouse-gas emissions never come up in those, “Hey, let’s reduce short-term emissions” discussions. Weirdly, the hard stuff—the 70% that steel and cement or aviation are great examples of—almost doesn’t come up at all.

But then, in 2015, at the COP21 [Sustainable Innovation Forum—held alongside the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Paris that year], it does come up. The French organizers wanted to do something a little different—and they wanted [Indian Prime Minister Narendra] Modi to come. And Modi didn’t want to come for the, “Hey, what’s your short-term reduction?” game—because India still needs five times as much electricity as they have today in order for much of the population to live even a basic lifestyle. And so he wasn’t going to come to that. But this side thing at COP21, which was called Mission Innovation, was not only focused on upping energy R&D budgets, but also on making sure there were private sector investors who are willing to take the risk—to turn these promising ideas into companies—if R&D labs turn the ideas out.

At that time, the bulk of the green investing was being done by people like John Doerr at Kleiner Perkins, or by Vinod Khosla’s venture funds—and, you know, they hadn’t had a very good track record. Kleiner Perkins had bet on Fisker [Automotive] instead of Tesla. There were a lot of solar panel [bets] that didn’t go well.

So I made a commitment to raise money to invest in the space.

And that became Breakthrough Energy Ventures—which is part of Breakthrough Energy, the umbrella for everything I do on climate. Breakthrough Energy has a few different areas to it, including an arm that focuses on policy solutions. But the venture investments are the biggest aspect at this time. (You can read our inside look at Breakthrough Energy here.)

So we raised that fund—with just over a billion dollars. And actually now, we’ve invested in 50 companies. That’s gone super well. We’ve gotten other people to invest. And by the time this book comes out [today, Feb. 16], we’ll have the billion dollars for what we’re calling BEV2, which will be the next 50 companies—you know, most of which will fail. And even the ones that succeed will be harder to get there than your typical software company due to the amount of capital involved and the kind of industrial partnerships you need to make them work. So it is quite a different kind of investing. My aim is to help scale that innovation.

But as you’re scaling up these investments and rallying other investors and policymakers to focus on these radical energy-related innovations, the pandemic hits. You yourself seemed to concentrate your attention—and your philanthropy—on finding therapies and vaccines for the coronavirus, which you spoke to Fortune about in September.

So the current generation, you gotta give ’em credit: Even through we’re in the midst of a pandemic, people truly care about the climate crisis, too. It’s not like it was during the financial crisis [of 2007–08] when people were like, “Hey, things are tough now, and that climate stuff, that’s way out there.” Even by 2010, if you polled the public, you’d find that interest in the climate had gone way down. It began to build up gradually over the next decade, but as we hit the pandemic, I thought, “Okay, what’s gonna happen?” But it’s actually gone up somewhat during the pandemic, which is kind of weird.

Likewise, look at the experts President Biden is picking—he’s putting climate people throughout the administration. And he says he’s focusing on several overlapping crises—you know, the pandemic and climate change are there at the same level, which is pretty impressive. And, of course, during both the presidential primaries and the election, the number of climate questions asked to the candidates was greater than we’ve ever seen. Or look at the European recovery plan, its capital investment is very climate-oriented too. Over a third of those dollars are connected to that.

So I feel lucky, in a way, that young people are making this topic important. And I didn’t do that when I was that age. You know, I wasn’t blocking traffic.

But my view is, “Hey, since you guys care about this so deeply—and you have the idealism to say, ‘Let’s do what it takes to get to zero by 2050’—you really deserve to have a plan where you work backwards and say, ‘Okay, what has to happen to steel and cement and aviation?’” The last thing you’d want is to have people think, “Oh, we’ll just make sure there’s a few more solar panels.” And then, 10 years later, emissions haven’t changed. And so unless there’s a plan, you’ll just end up generating a lot of cynicism and disappointment.

And so you decide to lay out that plan in a book.

Yeah, so my book is about the plan. It doesn’t explain why climate change is bad. Okay, I have one chapter on that. And I have a chapter on adaptation. But most of the book is this: “Hey, there are 51 billion tons of greenhouse-gas emissions. Here are the sectors that are responsible for those emissions.” And then we can look at each sector and say, “Okay, how much more expensive will it be to produce the same results with zero emissions?”

And that amount is the metric I called the Green Premium. So you can ask: “Okay, what’s the Green Premium today for cement? Is there a company out there whose technology can cut that in half? Is there any chance it can get to zero?”

Getting the Green Premium to zero is magic, which will happen for electric cars over the next decade. That is, you won’t have to government-subsidize the innovation or subsidize it from your individual budget. Once you’ve gotten that volume, and things have gotten cheaper, and you have the charging stations, etc., then the politicians can have some involvement. They can then say they’re going to ban gasoline cars by, you know, 2035, 2040, and the public doesn’t go, “What?!?”

If that Green Premium gets down close to zero, such a policy becomes possible. But we need to do the same across all the areas where we have lots of carbon emissions. And some of the areas, like in steel production or in making cement, are just superhard. So, anyway, that’s the basic thing.

One of the things I really like about the book is that the reader gets to experience your own learner’s journey into climate science. Every time you marvel about a fact—like that gasoline is cheaper than soda, for example—or explain why certain gases either absorb or reflect the sun’s radiation depending on their atomic makeup, it feels as though you are, somewhat joyfully, sharing that discovery with us. How conscious were you about sharing that personal journey of discovery in writing the book?

For me, all this stuff is so interesting. But when you read about it somewhere, it can often seem really opaque—like you’ll read an article that’ll say, “Oh, this reduction is equivalent to 10,000 houses or 40,000 cars.” There comes a point where you’ve really got to decide, “Am I going to take the effort to understand, numerically, what the total is or not—and then understand what these pieces of the total are?” I wanted to do the fairly simple math, so that when someone talked about the carbon reductions from those 10,000 houses or 40,000 cars, I could answer the question, “Okay, what percentage of the total carbon burden is that?”

When most people read those articles, they’re like, “It’s just gibberish.” And at first, when you try and get it, the number of energy measures are so large that, you know, it’s very confusing. For me, it was appealing to just map it to one thing.

I have to admit, my book owes a lot to Ken Caldeira and David Keith, who educated me and brought all those people in. And then there’s people like [former Microsoft CTO] Nathan Myhrvold and [prolific inventor] Lowell Wood, who, whenever I get confused about physics or chemistry, I just send them an email. And, of course, this guy Vaclav Smil, who’s written so many books—his fascination with what the industrial economy was like in 1800 and the great breakthroughs that followed has been an inspiration. I love this stuff. And it is actually simple. As with most areas of domain, there are only a few concepts, but you really have to get those concepts.

There’s the rate of energy, the amount of energy, and how long you can store it. For power, these all add up to “Can you use it when you want to use it?” And so Smil does these things where he shows, “Okay, how much does a city use, or how much does an individual household use?” And so you can get those numbers and that kind of common sense in your head.

As part of this, I actually took my son to a coal plant. And then to a cement plant and a paper mill just to see these things. Because we software guys are—I mean, I was terrible in the chemistry lab. So I was like, “Let’s just do the equations of chemistry, not, you know, do the stuff in those test tubes. I might blow something up.”

Growing up, I didn’t build little trains or planes or anything like that. So I’ve always felt, “God, that physical stuff, that’s the real thing.” I mean, somebody built those machines and those factories.

Anyway, yes, it’s been fun learning all this stuff. If I say to people how many hours I spent with those guys or how many books I had to read, I have to be careful because that sounds like bragging or something. But my greatest benefit is that I love being a student. And I love the idea that if I learn enough, it’ll actually be simple. I have enough confidence in that—and in smart friends who will help me get there—that, yes, I can say, “Okay, I’m going to learn about these things and eventually get to the point where it all fits together.”

At one point in the book, you seem to have gazed into the future. In the first galley that I read way back in the fall you mention “the U.S. withdrawal from the 2015 Paris Agreement” and say that it’s “a step that U.S. President Joe Biden later reversed.” It’s amazing that you knew that had happened long before the election.

Most of the work on this book was actually done about 10 months ago. I thought a lot about whether I should put the book out then. At first, the question was, if Trump gets reelected, then the U.S. won’t lead—and that would obviously affect our ability to do the things I call for in the book. You know, this book is about innovation, and the U.S. controls maybe greater than 50% of the innovation capacity in the world today—it’s in our universities, national labs, venture capital. And so if you don’t have the U.S. pushing its innovators, then that’s felt all around the world. Because in the U.S., we’re not just innovating for our own citizens, we’re also innovating on behalf of everyone else. If we learn to make clean [carbon-free] cement cheaply, then 30 years from now, when developing nations are housing their people, they’ll choose the clean cement.

And so, as I was writing, the last few chapters got really convoluted, having to couch things in, “Okay, if a Democrat gets elected…” and so forth. And then the pandemic hit, and I thought, “Oh, people might be a little distracted.”

So I just decided to do a postelection revision of the book and maybe add some technical advances. And so I did a whole run-through of the book after the election—and I was able to put a number of things in. On chapters one through nine, there were very few edits of any significance. On chapters 10 through 12, where I talk about government policy and the like, I actually did make a fair number of changes. Even with Democrats controlling the White House and Congress, with the Senate nearly evenly split—and with the kind of deficit we’ve gotten into—we’re going to have to come up with a plan that doesn’t require a huge level of resources. But that’s very doable. I’m actually quite optimistic about that.

The politics of this are so complex. In your road map in Chapter 11, you suggest both incentives and disincentives or penalties, in terms of policy initiatives—both carrots and sticks. But in the past, we’ve seen that the sticks are much harder to put in place. In the case of the Affordable Care Act, for example, where there was a Democratic majority in the executive branch and in both houses of Congress, the mere concept of an individual mandate and an associated penalty ended up causing a legislative civil war—one that’s still going on to this day. So when I came to the part in your book about setting a price on carbon, effectively, a “carbon tax,” big enough to offset the Green Premium, I wondered how confident you were that something like that could actually happen in any near-term timeline? As you write: “Putting a price on emissions is one of the most important things we can do to eliminate Green Premiums.”

Well, without innovation, even if carbon capture can come down to, say, $100 a ton, we’d still have an enormous challenge because we’re emitting 51 billion tons of carbon a year. And so somewhere in the world you’d have to find $5 trillion that you would spend per year. That’s over 5% of the world economy. And there’s just no way, not a chance, that that happens.

Of course, any kind of carbon tax is politically very difficult. When France tried to raise their price for diesel, people shouted, “Hey, you can’t do that!” And inevitably such things are always cut because they fall disproportionately on people. You can try and offset that. But in that French case, the people who lived outside the cities and had to drive longer distances felt the elites in the cities were ignoring them—which is, you know, the general political phenomenon in all rich countries now. In the end, they got that diesel tax repealed.

So there’s not much willingness of the public to pay now to avoid these negatives—most of which are far out in the future. I mean, yes, there are some weather things—forest fires, very hot days—that are happening now. And I’m glad people are paying attention to those. But if we don’t act now, these will be nothing compared to what we’ll get in 2080 and 2100, and that will be even more so for anyone living near the equator. So going outdoors in India in 2100 during their summer months is gonna be unbearable. Outdoor work will be impossible. The body can only sweat so much.

Near the end of your book, as you’re summarizing your plan for getting to zero emissions, you talk about “accelerating the demand for innovation.” That notion is really critical, it seems, to success—and it also seems different from much of what you’ve done in your philanthropic work. In the foundation you run with Melinda, you have often funded the supply of innovation—investing in lots of these startups. But creating markets in some places where they don’t exist—building the demand side—is a different sort of challenge.

In the drug industry, for instance, Big Pharma companies provide a market for innovation through legions of biotech startups, competing to in-license experimental drug candidates that might be promising in one indication or another. Is there a similar model on the climate front, with big energy companies providing a ready market for zero-carbon discoveries from energy startups? Or as with defense industry innovation, will the “market” have to be provided by governments?

You know, energy’s a lot harder. Software, by comparison, is the easiest in this regard. Medicine is kind of in the middle. And these climate-related things are the hardest. In software, there’s always some customer who doesn’t like the current software—and who thinks that yours is either simpler, cheaper, or has more functionality in some area. So you carve off that piece from whoever’s dominant, and you can go after a certain set of customers because you’ve matched up to their needs better. That provides a ready market for software innovators.

Likewise for medicine. You look at the various diseases, and maybe you make something that’s oral instead of injected or that reduces some side effect. Or hopefully, every once in a while, you find a completely novel way to attack a disease that there is no medicine for. There you also have all the regulatory issues and inspection issues and side effects, etc.

With climate, the thing that’s so difficult is that when you make steel—clean steel, there is no added use or benefit beyond what it does for the planet. The mere fact that you’ve made it slightly differently than the historically accepted process is likely to provoke questions among buyers: “Does it last, does it get brittle, does it rust?” People will look askance at any change. That’s because steel is so reliable. Just as cement is. They have a formula for exactly what goes into it. They don’t test its characteristics; they just test that you followed the formula. And so there’s no niche in the marketplace that inherently wants to pay more for clean steel or clean cement.

Now, what happened with solar panels was that there were satellites where you needed a source of energy, and the solar panels were the only way to do it. And you got Germany and Japan to buy them even when it was non-economic. Not a huge volume—but enough volume that you started this learning curve. And then other countries, including the U.S., put their tax credits in, and you got to expand this learning curve. And we’ve seen the learning-curve pattern play out with wind and lithium-ion batteries. Those are three miracles that have happened.

Now, sadly, most people think, “Okay, just because you make batteries good enough for cars, we can make them good enough for the entire electrical grid—and we’ll have another miracle there.” Well, they don’t realize that many attempts at miracles like, for instance, fuel cells, or hydrogen-powered cars, have yet to pan out.

There are other complications with innovating, for example, in the case of fission-powered nuclear reactors. Here, the cost and the fear of safety issues are such that, unless we rebuild the reactor with a whole new design that’s utterly different in terms of economics and safety, that will be a dead end. And so that’s what I’m trying to do with [nuclear energy company] TerraPower [where Gates serves as chairman of the board].

And so if you project the successes we’ve had onto all these areas, you can end up thinking this thing is far easier than it is. And your question’s a super good one because that’s one piece in the overall strategy described in the book, having a buyer for that clean steel.

To that end, say the Green Premium is $100 a ton today. If someone were to come along and start a clean-steel company that has a mere $50-per-ton premium, you’d go to that person and say, “Hey, hallelujah, good job, buddy!” But in fact, that’s a zero-sized market, because $50 more per ton just means it costs more money.

Now, what we’re going do is to try and get richer companies, including the big tech companies, to agree that whenever they build a new building, they’re going to use 20% clean steel. And their reward is they get to say, “Hey, we used 20% clean steel.”

So we have to create the demand side. Your question is a super good one. I, of course, love the supply side of innovation. You know, to go find the professor, go find the guy with the crazy idea. And so Breakthrough Energy Ventures has lots of those. Among the 50 companies in the fund is one where a guy has figured out how to store energy long-term by pumping water into the ground and storing it between underground layers of rock. It takes energy to pump it down, but that can be done when electricity is abundant. Then, when he wants energy back, he opens the well and the pressurized water rushes out, powering a turbine.

And that shouldn’t work. The company’s called Quidnet. I think there’s some reference to Harry Potter, or something. I don’t know why. I should know that. But anyway, funding that guy is an example of what we like to do. That’s the supply side of innovation.

But you need the demand side, too. Take these artificial meat companies. Well, amazingly, their market is driven by consumer choice. When Burger King began offering the Impossible Whopper, the demand was super high, which is good.

But in steel and cement, because the green-tech is so obscure, it’s much harder to create that demand. In the case of aviation fuel, the extra cost of a clean fuel is going to mean your plane ticket is, like, 25% higher. You know, people might say at a cocktail party that they’re glad to pay that 25%. But actually, I doubt that when push comes to shove, that such an effort can be funded by consumers paying the full cost of that Green Premium.

So it is much harder than creating a marketplace for innovation in the software or even medical industries. And that’s probably why Breakthrough Energy Ventures has a 20-year life span and a different set of incentives. It has investors who know that most of the companies in there are likely not to succeed.

Have you have ever thought of opening up the fund, or one like it, to public investors and letting people buy shares in order to help create that demand?

Yeah. We haven’t yet formulated this, but I do think being able to say to companies—as they figure out what their carbon emissions are and the cost of that, estimated at some price per ton—that they should be willing to write a check out to mitigate that. And those checks, in principle, could finance a fund that does an auction to say, “Okay, who can give us green steel at the lowest price? Who can give us green cement?”

And so I like that idea of getting, both individuals who feel guilty about their carbon footprint, and companies—particularly quite profitable ones—who could underwrite a buying fund that does what the space industry did for solar panels: that is, create the demand side. That is something I want to organize. And, you know, people will say, “Okay, I’m a member of this Breakthrough Energy buying effort” at some level and be proud of it.

You could do as Warren Buffett does at Berkshire Hathaway and create “A” shares for rich companies and “B” shares for the rest of us.

Yeah, platinum and gold.

If I might draw a strategy from watching your long philanthropic career it is that you seem to have structured your efforts around what one might call first movers. If you can fix X, then you can reduce all the bad outcomes that cascade from X.

So when you and Melinda began the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, a logical first step was to invest in global health, working on ending scourges like malaria, diarrheal disease, neglected tropical diseases, polio, and others. Reducing the number of children who get sick and die each year was not only a good thing in itself, of course, but it would also in theory cause a cascade of good effects: reducing endemic poverty, for one thing, by helping to ensure that there were more healthy, productive citizens to strengthen a developing nation’s economy.

So if you fix one thing, you can have a positive effect on something downstream. You see the same multiplier effect when you look at your foundation’s investments in education—and particularly in educating young women and girls. As Melinda says, the No. 1 indicator of under-5 mortality is the educational status of the mother. So fix that, and you can lift generation after generation out of poverty.

You can follow that same thread with your other major investments: trying to improve sanitation, for example, which will reduce cholera, typhoid, diarrheal disease, dysentery, and Lord knows what else. And so forth.

So now, you’ve turned in a big way to climate change—which, arguably, might be the ultimate “first mover” in a chain of problems, at least if we don’t stop it in its tracks: Fix climate change…or the world ends. If that reasoning is true, does your focus on climate change become even more dominant in this mix of causes that have grabbed your and Melinda’s attention over the years? And how do you begin to triage all these urgent demands for your time, attention, and money?

Yeah, in the foundation space—in the global health stuff—the impact per dollar is huge. We’re saving lives for less than $1,000 per life saved. And there’s this sort of market failure that, because malaria doesn’t exist in rich countries, there’s no market signal that innovators should come up with drugs and vaccines for malaria, or an overall strategy to get rid of it. The poor countries where it’s endemic don’t have the resources to solve malaria.

When I gave the first $30 million to fighting malaria, I became the biggest funder in that effort. You could say that’s a sad thing—or an opportunity to dramatically push for change. People in climate talk about carbon capture. Well, I’m the biggest funder of those companies, and that amounts to tens of millions of dollars. That includes companies like Climeworks, Carbon Engineering, and Global Thermostat. There’s like four or five companies in that carbon capture space. And fortunately, there will be more because there are several different approaches there.

Whenever I see something where the investment, if it succeeds—in terms of the societal impact per dollar—is like a thousand times return, I feel like the venture capitalist putting early money into Google or something. You know, I’m drawn in. And seeing those potential innovations succeed over time, that’s what I enjoy doing. I enjoy gathering the kind of people who can see those things and be willing to be patient. And maybe even, in some cases—like preventing or curing HIV—bet on multiple potential paths, knowing that a number will fail. But still, even if you add all that money to the different approaches, even if just one works, it’s very, very magical.

So it’s kind of an innovation mindset. There are things like improving U.S. education where, as yet, if you take broad indicators such as, “How good are U.S. students at math—or reading and writing?” or “How many kids drop out of college?” we haven’t had the kind of scale impact we’ve had on our global health work. And yet, we still believe we can make an impact. In fact, we doubled down on this effort. The idea that now more kids will actually have laptops and Internet connection, which got pushed very forward during the pandemic, has us really building a new generation of curriculum that’s very different.

So hope springs eternal even in the areas where, so far, you’d have to say the impact has been almost hard to detect. You don’t know in advance what’s going to work. And most efforts to fix a problem turn out to be harder than you think. A few—like when I put money into Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods—I would have said to you, at the outset, that “fixing meat” was as hard as creating zero-carbon steel and cement. And now, though it’s not yet solved, there’s a pathway. It’s almost like with electric cars where, as the cost goes down and the quality—in this case, of the various ways of making synthetic meat—improves, the Green Premium will go to zero. That one actually surprised me in how quickly it went.

One thing that surprised me in the book was what seemed like your belief in a natural limit to energy storage. There are some who still hold out hope for the near-infinite storage battery—or at least one with hugely expanded capacity—which would make storing energy from the sun or wind or whatever far more feasible in a grid-like way. To me, that was one heartbreaking part of the book. It’s hard to come to grips with the idea that there’s no Moore’s law for energy storage.

Yeah, the fact that Moore’s law has worked as long as it has is super mind-blowing. That software and digital stuff makes people think miracles are always possible—whereas this is more like what’s happened to gas mileage over a hundred years. You know, if Edison came back, he would look at our batteries and say, “Wow. These batteries are about four times better than my lead acid batteries. Good job.” That’s a hundred years of battery innovation.

And people get confused between batteries for electric cars and what range you get—in which just expanding range by another factor of two makes that really good—and batteries for grid storage where the aim is to collect solar energy in the summer and use it in the winter. So in that example, for that whole battery, you’re getting one benefit. One time per year you get to pull that energy out.

The cost and scale of that is so difficult. You know, we’re more than a factor of 20 away from it. I’ve lost more money on battery companies than anyone. And I’m still in, like, five different battery companies—a few directly and a few through BEV [Breakthrough Energy Ventures]. There are only three ways to solve the electric grid problem: one is a miracle in storage, the second is nuclear fission, and the third is nuclear fusion. Those are the only possibilities.

Thank you, Bill.

Thank you so much. This was fun.