|

上世紀(jì)90年代,,互聯(lián)網(wǎng)曙光初露——如同你認(rèn)識(shí)的每個(gè)人一樣,你也有著滿腦子的互聯(lián)網(wǎng)天才創(chuàng)意,。因緣際會(huì),,你甚至與硅谷最炙手可熱的風(fēng)險(xiǎn)資本家之一說(shuō)上了話。這是你的地盤,,這里星火已燃,,東風(fēng)將起——你就要在互聯(lián)網(wǎng)上賣書了。(風(fēng)投卻打起了呵欠,。) 你告訴風(fēng)投,,你將用數(shù)年甚或數(shù)十年打造公司的科技基礎(chǔ)設(shè)施和倉(cāng)儲(chǔ)能力,不懈地關(guān)注客戶體驗(yàn)——你甚至將公司命名為“Relentless.com”(譯注:Relentless的意思是堅(jiān)持不懈),,以順應(yīng)那席卷而來(lái)的客戶中心化浪潮,。當(dāng)然,你也得搞搞降價(jià)促銷來(lái)?yè)Q取市場(chǎng)份額,,還得抓好物流環(huán)節(jié),,但假以時(shí)日,你將達(dá)到現(xiàn)象級(jí)的規(guī)模,,可以銷售任何東西——沒錯(cuò),,是“任何”東西——給所有人。你將建立“銀河系最大的商店”,。 風(fēng)投開始動(dòng)心,。當(dāng)他們找你要一些實(shí)打?qū)嵉呢?cái)務(wù)預(yù)測(cè)數(shù)據(jù)時(shí),你眼睛都不眨一下:上市之前,你和投資人當(dāng)然要大筆投入現(xiàn)金,。接下來(lái)是連續(xù)17個(gè)季度的赤字,,這時(shí)你會(huì)多費(fèi)點(diǎn)口水四處交涉。頭9年里你將帶著30億美元的負(fù)債運(yùn)營(yíng)——直到最終開始盈利,,但在十年甚至更長(zhǎng)時(shí)間里,,平均利潤(rùn)薄到只有2%。 如果在電梯里推銷這個(gè)項(xiàng)目,,通常來(lái)說(shuō)當(dāng)電梯到達(dá)一層時(shí)故事也就結(jié)束了,,但如果劇情不是這樣,那后面一定有精彩好戲,。亞馬遜(Amazon)的創(chuàng)業(yè)故事現(xiàn)在已經(jīng)成為公司銘刻在冊(cè)的傳奇,,實(shí)際上杰夫·貝佐斯最初真的給自己的網(wǎng)站起名為“Relentless.com”,直到后來(lái)他改變了主意(你可以試試在瀏覽器輸入這個(gè)網(wǎng)址),。當(dāng)時(shí)的出資人就是來(lái)自Kleiner Perkins公司的傳奇投資人約翰·杜爾,, 1996年他給亞馬遜投了最初的800萬(wàn)美元,三年后又投了另一個(gè)看似荒唐卻雄心勃勃的初創(chuàng)企業(yè),,名叫谷歌(Google),。 杜爾在貝佐斯身上(同樣也在拉里·佩奇和塞吉·布林身上)看到的不只是遠(yuǎn)大的商業(yè)眼光,還有把事情干到底的瘋狂韌性,。其他人也看到了這一點(diǎn),。摩根士丹利(Morgan Stanley)的分析師瑪麗·米克爾在華爾街是出了名的亞馬遜看漲派。1999年,,她掃除了業(yè)界對(duì)亞馬遜“激進(jìn)”投資于基礎(chǔ)設(shè)施的普遍擔(dān)憂,,稱亞馬遜的這一戰(zhàn)略是“理性的沖動(dòng)”。美盛集團(tuán)(Legg Mason)的前任基金經(jīng)理比爾·米勒連續(xù)15年跑贏標(biāo)普500的記錄無(wú)人能及,,他在早期大筆投注亞馬遜,,911之后在亞馬遜每股從三位數(shù)跌到6美元時(shí)更是雙倍下注,最后股價(jià)回升?,F(xiàn)如今亞馬遜每股超過1600美元,,相較于1997年亞馬遜上市時(shí)除權(quán)調(diào)整后的收盤價(jià),,盈利106,669%,。 若當(dāng)事后諸葛,制造這種傳奇很容易,。任何人只要看看歷史股價(jià)圖,,就能知曉上一代商界中誰(shuí)將成為贏家或輸家。而要想增長(zhǎng)智慧,,歷史是最好的老師,。亞馬遜令人矚目地崛起為今年《財(cái)富》美國(guó)500強(qiáng)中排名第八的企業(yè),因此貝斯·考維特專門就亞馬遜的話題在本期雜志上撰寫了主題文章,。文章揭示了一個(gè)核心的應(yīng)該刻入史冊(cè)的管理理念:創(chuàng)立偉大的公司,,不僅需要持續(xù)不斷地專注于把現(xiàn)在的事情做好(商業(yè)勵(lì)志大師稱之為“執(zhí)行力”),,還需要同樣持續(xù)不斷地專注于把將來(lái)的事做得更好。幾年前貝佐斯告訴我的同事亞當(dāng)·拉辛斯基,,“亞馬遜有三條宗旨:長(zhǎng)線思維,,客戶至上,樂于創(chuàng)新,?!? 我們這個(gè)時(shí)代最負(fù)盛名的公司創(chuàng)始人——蘋果(Apple)的史蒂夫·喬布斯,沃爾瑪(Walmart)的山姆·沃爾頓,,聯(lián)邦快遞(FedEx)的弗雷德·史密斯,,西南航空(Southwest)的赫伯·凱勒爾,Intuit公司的斯考特·庫(kù)克,,Salesforce的馬克·貝尼奧夫——本能地就知道這些,。這一理念被一個(gè)又一個(gè)的商學(xué)院案例強(qiáng)化,被最受擁戴的投資人宣講,。沃倫·巴菲特的投資理念被投資界奉為圭臬,,他常說(shuō),最好的持股期限是“永遠(yuǎn)”,。 盡管拿什么指標(biāo)來(lái)定義長(zhǎng)期專注的公司并無(wú)清晰定論,,從有限的資料來(lái)看,他們確實(shí)是更好的投資對(duì)象,,至少好過那些短線思維的公司,,也就是那些追求季度盈利目標(biāo)、回購(gòu)存貨以提升股價(jià),、削減研發(fā)投入,、砍掉對(duì)技術(shù)和員工的關(guān)鍵投資的那些公司。標(biāo)普全球(S&P Global)去年10月的一份研究發(fā)現(xiàn),,對(duì)于大中型企業(yè)來(lái)說(shuō),,與那些更關(guān)注“下一季度營(yíng)收”的公司相比,“具有長(zhǎng)遠(yuǎn)性”的公司在過去20年里持續(xù)帶來(lái)更高的回報(bào),。(《財(cái)富》雜志與波士頓咨詢公司(Boston Consulting Group)在去年11月共同公布了具有前瞻性的公司名單——財(cái)富50強(qiáng)企業(yè)——他們穩(wěn)步再投資于產(chǎn)能以持續(xù)增長(zhǎng),。) 麥肯錫全球研究所(McKinsey Global Institute)在2017年2月的一份研究中也同樣揭示,有遠(yuǎn)見的公司財(cái)務(wù)表現(xiàn)也更好,。自2001年至2014年,,資料庫(kù)里那些有長(zhǎng)遠(yuǎn)打算的600家大中型公司,平均業(yè)績(jī)?cè)鲩L(zhǎng)比其他公司多47%,,在收入增長(zhǎng)和市場(chǎng)資本總額方面的表現(xiàn)也更好,。麥肯錫的研究者發(fā)現(xiàn),盡管在金融危機(jī)期間,這些公司的股價(jià)跌得也更多,,但回調(diào)也更快,。從更宏觀的經(jīng)濟(jì)角度來(lái)看,有遠(yuǎn)見的公司在同一時(shí)期也創(chuàng)造了更多的就業(yè),。 既然如此,,為何那么多公司還是習(xí)慣性地只關(guān)注下一季度?你猜對(duì)了,,是因?yàn)槿A爾街,。麥肯錫研究者發(fā)現(xiàn),十個(gè)經(jīng)理和主管中就有九個(gè)備受壓力,,要在兩年甚至更短時(shí)間內(nèi)提交可觀的業(yè)績(jī),。這些壓力有許多是來(lái)自激進(jìn)的對(duì)沖基金,這些基金大多茹毛飲血,,追求短期內(nèi)的投資回報(bào),。 |

It’s the 1990s, the dawn of the Internet age—and you, like everyone you know, has a genius of a dotcom idea. Somehow, you get in to see one of the hottest venture capitalists in Silicon Valley. Your pitch, fired up and ready: You’re going to sell books over the Internet. (The VC yawns.) You tell him that you’re planning to spend years, or really decades, building up technological infrastructure and warehouse capacity, focusing relentlessly on customer experience—you’ll even call the company “Relentless.com” to capture that ferocious customer-centricity. Sure, you’ll have to discount prices to gain market share, and take a hit on delivery, but in time you’ll have the phenomenal scale to sell “Anything?…?with a capital ‘A’?”—to everyone. You’ll be “earth’s biggest store.” The VC stirs a bit. When he asks you for some hard-number projections, you don’t bat an eye: You and your investors will bleed cash, of course, before you go public. Then you’ll lose gobs more, going 17 straight quarters in the red. You’ll be in the hole about $3 billion in your first nine years as a going concern—and when you do eventually turn a profit, the margins will be razor thin for a decade or more, averaging about 2%. As elevator pitches go, this one would almost certainly end on the first floor. Except it didn’t. The story of Amazon.com—Jeff Bezos did indeed toy with the name “Relentless.com” before changing his mind (Go ahead: Type it in your browser)—is now engraved into the corporate mythos. The backer was the legendary John Doerr of Kleiner Perkins, who invested an initial $8 million in the company in 1996, and who three years later would back another ludicrously ambitious startup called Google. What Doerr saw in Bezos (and in Larry Page and Sergey Brin, for that matter) wasn’t just a grand business vision but also the maniacal tenacity to see it through. Others saw it too: In 1999, Morgan Stanley analyst Mary Meeker, a prominent Amazon bull on Wall Street, brushed off concerns of the company’s “aggressive” investment in its infrastructure, calling the strategy “rational recklessness.” Bill Miller, the former Legg Mason fund manager whose 15-year market-beating streak remains unmatched, invested early and heavily in Amazon—and then doubled down on the stock as it careened from triple digits to six bucks a share (after 9/11) and up again. It’s now trading above $1,600, a 106,669% gain over the split-adjusted closing-day price of its 1997 IPO. Such legend-making is easy in hindsight, of course. Everyone with access to a historical stock chart can plot the last generation’s certain winners and losers. That said, when it comes to gaining wisdom, the past is one of best teachers we have—and the striking rise of Amazon, No. 8 on the Fortune 500 and the subject of a profile by Beth Kowitt this issue,offers a core management lesson that ought to be carved in tablets by now: Building a great business requires not only a relentless focus on doing things well this minute (what business-book thumpers call “execution”), but also an equally relentless focus on doing things better in the future. As Bezos told my colleague Adam Lashinsky some years ago, “The three big ideas at Amazon are long-term thinking, customer obsession, and a willingness to invent.” Most of the celebrated company builders of our era—Apple’s Steve Jobs, Walmart’s Sam Walton, FedEx’s Fred Smith, Southwest’s Herb Kelleher, Intuit’s Scott Cook, Salesforce’s Marc Benioff—have known that instinctively. It’s a message reinforced by one biz-school case study after another and preached by the most acclaimed of investors. Warren Buffett, whose investing horizon is the horizon, likes to say his preferred holding period is “forever.” While the parameters of what defines a long-term-focused company are still somewhat squishy, the limited evidence so far suggests that they make better investments too. At least compared to short-termers: companies that are chasing quarterly earnings targets, buying back stock to pump their share prices, cutting R&D, and slashing other key investments in technology and people. An October study by S&P Global found that an index of large and midsize companies that, it says, “embody long-termism” had consistently higher returns on equity over the previous 20 years than various quartiles of companies with more of a “next quarter” focus. (Working with the Boston Consulting Group, Fortune also unveiled in November a list of forward-looking companies—the Future 50—that steadily reinvest in the capacity to grow.) A separate February 2017 study by the McKinsey Global Institute, likewise, found far better financial performance from far-horizon companies. From 2001 to 2014, long-term firms, drawn from a data set of more than 600 large and medium-size companies, had an average of 47% greater revenue growth than other firms as well as faster growth of earnings and market capitalizations. Although share prices for this group did suffer more during the financial crisis, they also recovered more quickly, the McKinsey researchers discovered. And from a broader economic standpoint, the farsighted companies also created a lot more jobs than other firms did during the same period. So why do so many companies still habitually manage to the next quarter? You guessed it: Wall Street. Nearly nine in 10 executives and directors feel mounting pressure to deliver strong financial results within two years or less, McKinsey found. And much of that push is coming from activist hedge funds, many of which are incentivized to goose their own investment returns in the near term. |

|

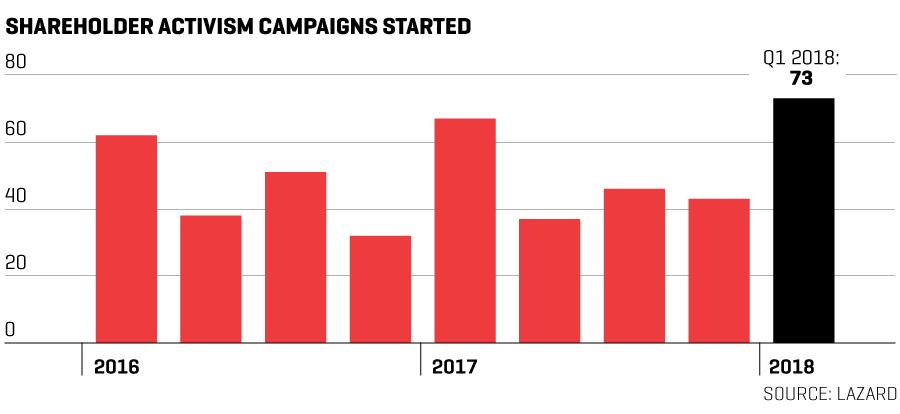

據(jù)追蹤股東激進(jìn)主義運(yùn)動(dòng)多年的拉扎德公司(Lazard)的消息,,2018年的第一季度,,發(fā)生了創(chuàng)紀(jì)錄的73場(chǎng)股東激進(jìn)主義運(yùn)動(dòng),涉及250億美元的資本,。這些運(yùn)動(dòng)有些是要求分解或賣掉公司,;有些要求股票回購(gòu)或者董事會(huì)席位(激進(jìn)者僅在第一季度就贏得了65個(gè)董事會(huì)席位)。據(jù)拉扎德公司透露,,另一些只是對(duì)“惡意競(jìng)購(gòu)”感興趣,,即為了阻止兼并收購(gòu)項(xiàng)目進(jìn)行,或者試圖影響談判,。 麥肯錫咨詢公司(McKinsey & Company)的全球管理伙伴鮑達(dá)民十多年來(lái)一直致力于鼓勵(lì)企業(yè)放眼長(zhǎng)遠(yuǎn),,不論在辦公室還是董事會(huì)。他說(shuō):“不可否認(rèn)有些激進(jìn)者倒是更偏長(zhǎng)遠(yuǎn)考慮些,?!边@些投資者經(jīng)常能讓一個(gè)長(zhǎng)遠(yuǎn)戰(zhàn)略得到更好的執(zhí)行,也能讓公司管理層在關(guān)鍵環(huán)節(jié)行動(dòng)得更快,。 但大多數(shù)激進(jìn)者還是追求短期利益——而且他們的影響力常常超過其股份比例,。“這其中的挑戰(zhàn),,部分在于有些人能坐在多個(gè)董事會(huì)席位上,,”鮑達(dá)民說(shuō),“有這么的股東激進(jìn)運(yùn)動(dòng)在進(jìn)行,,很可能有些人有股東激進(jìn)運(yùn)動(dòng)的經(jīng)驗(yàn)并會(huì)分享給董事會(huì)。把其他董事會(huì)成員嚇破膽,就是個(gè)不錯(cuò)的方法:‘天哪,,你才不想那么做,!就像你剛從戰(zhàn)場(chǎng)回來(lái),你根本不想再返回,?!?” 對(duì)于長(zhǎng)效管理來(lái)說(shuō),更大的威脅是CEO薪酬,,說(shuō)這話的是《財(cái)富》雜志撰稿人布萊恩·杜梅,,他與丹尼斯·凱利、邁克爾·尤西姆,、以及羅德尼·澤梅爾合著了一部重要的新書《做多:為何遠(yuǎn)見是最好的短期策略》(Go Long: Why Long-Term Thinking Is Your Best Short-Term Strategy)?,F(xiàn)今大多數(shù)CEO的報(bào)酬,部分體現(xiàn)在其任期內(nèi)的股價(jià),。股東代言人——比如領(lǐng)航投資(Vanguard)的董事長(zhǎng)比爾·麥克納布——就在推動(dòng)讓CEO離職五年后才獲得一半或更多的股票回報(bào),,而埃克森美孚(Exxon Mobil)實(shí)際上已經(jīng)這么做了,。 個(gè)中原理很簡(jiǎn)單:“如果你是石油公司的CEO,,你可以決策削減勘探費(fèi)用,這樣一來(lái)支出減少,,你的收入就突然很美妙了,,”杜梅說(shuō),“但5年后,,你的繼任者就有麻煩了,。” 這就是短期利益追逐者的問題所在,。大部分的美國(guó)股東,,即便不是幾十年,也的確多年持有股票,。但不可避免的是,,如果經(jīng)理人追求短期目標(biāo),這個(gè)國(guó)家的長(zhǎng)期投資人就輸了,。(財(cái)富中文網(wǎng)) 此文首發(fā)于《財(cái)富》雜志2018年6月1日刊 譯者:Hank |

A record 73 activist campaigns, deploying some $25 billion in capital, were initiated in the first quarter of 2018, according to Lazard, which has been tracking shareholder activism for years. Some campaigns push for a breakup or sale of the business; some for share buybacks or a seat on the board (activists won 65 board seats in the first quarter alone). Others are merely interested in “bumpitrage,” Lazard says—that is, to block an M&A deal from going through or to influence its negotiations. “To be sure there are some activists who actually behave a little more long term than we give them credit for,” says Dominic Barton, McKinsey & Company’s global managing partner, who has been championing efforts to encourage long-termism in corporate suites and boardrooms for more than a decade. These investors can often push for better execution of a far-thinking strategy and get company managements to move much faster in critical areas. But short-termers dominate this crowd—and their influence is often outsize compared with their shareholdings. “Part of the challenge is that people often sit on multiple boards,” says Barton. “Given the amount of activist activity going on, someone will very likely have had experience with a campaign and will share it with the board,” he says. “It’s a good way to scare the hell out of the other members: ‘My God, you don’t want to go through this! It’s like you’ve come back from a war. You just don’t want to go there.’?” An even bigger threat to long-term managing is the way we do CEO compensation, says Fortune contributor Brian Dumaine, coauthor with Dennis Carey, Michael Useem, and Rodney Zemmel of an important new book titled, Go Long: Why Long-Term Thinking Is Your Best Short-Term Strategy. Today, most chief executives are rewarded based partly on how the stock performs during their tenure. Shareholder advocates like Vanguard chairman Bill McNabb are pushing instead to have half or more of the stock compensation vest five years after a CEO leaves the job—which is what Exxon Mobil actually does. The rationale is straightforward: “If you’re the CEO of an oil company, you can decide to cut way back on exploration and you’d have lower capital spending and suddenly your earnings are going to look great,” says Dumaine. “But five years down the road your successor is going to be in trouble.” That right there is the problem with short-termism. The great majority of shareholders in the U.S. do hold their stocks for years, if not decades. Inevitably, when managers chase the next quarter, it’s a nation of long-term investors who lose out. This article originally appeared in the June 1, 2018 issue of Fortune. |